The Physics of Fidelity: Understanding Open-Air Acoustics Through the Lens of Legacy Engineering

Update on Nov. 22, 2025, 7:32 p.m.

In the world of personal audio, there is often a misconception that high fidelity is strictly a function of price. Consumers are bombarded with marketing for noise-canceling wireless earbuds that cost hundreds of dollars, leading many to believe that “good sound” is a luxury commodity. However, sound engineering is governed by physics, not just pricing strategies. By examining legacy acoustic designs, specifically the principles behind lightweight, open-back headphones, we can uncover how accurate sound reproduction is achieved through material science and structural geometry rather than electronic processing.

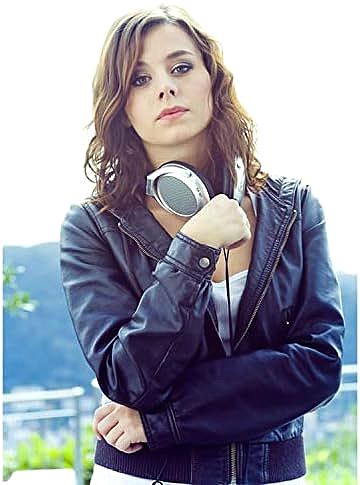

To illustrate these acoustic principles, we will examine the engineering choices found in the Koss UR40, a model that serves as a distinct example of prioritizing driver technology and acoustic openness over modern creature comforts.

The Open-Air Paradox: Isolation vs. Soundstage

The most significant architectural decision in headphone design is the treatment of the rear of the driver enclosure. Most modern consumer headphones are “closed-back,” meaning the outer shell is solid. This seals the music in and noise out, creating a pressurized chamber. While excellent for commuting, this design often results in a “box-like” resonance, where sound waves bounce around inside the cup, muddying the audio image.

Conversely, “open-back” or “semi-open” designs, like the architecture observed in the Koss UR40, utilize screened ear cups. This allows air to flow freely through the driver.

Why Airflow Matters for Audiophiles

When a speaker driver moves back and forth to create sound, it creates pressure. In a closed system, this pressure builds up behind the driver, resisting its movement—imagine trying to push a piston into a sealed tube. By venting the back of the ear cup with a mesh screen, the driver can move more freely.

This results in two specific acoustic characteristics:

1. Expanded Soundstage: The sound feels like it is originating from the room around you, rather than dead-center inside your skull. It mimics the natural way we hear sounds in the real world.

2. Natural Decay: Notes fade out naturally without the artificial reverberation caused by plastic enclosures.

However, this design represents a classic engineering trade-off. The “hear-through” sound described in technical specifications means that isolation is virtually non-existent. External noise enters, and your music leaks out. For the critical listener, this is a necessary sacrifice for spatial accuracy.

Material Science: The Role of Titanium

The heart of any headphone is the driver—the component that converts electrical signals into sound waves. The ideal driver diaphragm must be two contradictory things: infinitely rigid (to prevent warping) and infinitely light (to move instantly).

Standard budget headphones often use Mylar or basic plastic diaphragms. While functional, these materials can flex under stress, causing distortion, particularly at high frequencies. This is where material science differentiates “producing sound” from “reproducing audio.”

The integration of a titanium coating on high-polymer diaphragms, a feature central to the UR40’s performance profile, addresses this rigidity problem. Titanium adds significant stiffness without adding excessive weight.

- Transient Response: A stiffer, lighter driver can start and stop moving more quickly. In musical terms, this means the “snap” of a snare drum or the pluck of a guitar string is rendered with precision.

- Frequency Extension: Enhanced rigidity allows the driver to vibrate at higher frequencies without breaking up, contributing to the reported 15–22,000 Hz frequency response. This coverage extends beyond the typical human hearing range, ensuring that the audible upper harmonics remain clean and distortion-free.

The Structural Trade-off: Weight and Durability

One of the most polarizing aspects of high-fidelity audio equipment is build quality versus weight. Achieving a “barely there” wearing experience often requires the extensive use of lightweight polymers.

The Koss UR40 is engineered to be exceptionally light, weighing just over 6 ounces. To achieve this, the chassis is constructed almost entirely of plastic, with a simple mesh sling for a headband. From a durability standpoint, this minimalist construction is a point of vulnerability. The frame does not possess the ruggedness of heavy studio monitors or metal-encased fashion headphones.

This highlights a “Function over Form” philosophy. Every ounce of weight saved is an ounce less pressure on the neck and head, allowing for hours of listening without fatigue. The mesh sling design distributes what little weight exists across a broad surface area, eliminating the “hot spots” common with heavier, padded headbands. However, users must treat such equipment with the care typically reserved for precision instruments rather than rugged outdoor gear.

Electrical Compatibility: Understanding Impedance

The final piece of the puzzle is Impedance, measured in Ohms (Ω). This specification dictates how much power is needed to drive the headphones properly.

- Low Impedance (<32Ω): Easy to drive, but often susceptible to background hiss (noise floor) from the amplifier.

- High Impedance (>100Ω): Requires dedicated amplification to reach listenable volumes.

With an impedance of 60 Ohms, the UR40 occupies a “sweet spot” in audio engineering. It is high enough to dampen the background hiss found in some computer sound cards or cheaper audio interfaces, providing a cleaner background for the music. Yet, it remains sensitive enough to be driven to adequate volumes by standard portable devices without the absolute need for an external amplifier. This makes it a versatile reference point for listeners moving between dedicated home setups and mobile listening.

Conclusion: The Value of Acoustic Transparency

Understanding audio equipment requires looking past the packaging and into the physics. The combination of semi-open architecture and titanium-coated drivers offers a glimpse into the world of audiophile listening—a world where spatial imaging and transient response take precedence over booming bass or noise isolation.

While the structural materials of entry-level audiophile gear like the Koss UR40 may not inspire the same confidence as milled aluminum, the acoustic engineering within tells a different story. It serves as a reminder that in the pursuit of high fidelity, the most important components are often the ones you cannot see, but definitely can hear.