Hypertech X EP1 Bluetooth Headphones: The Must-Have Active Noise Cancelling Neckband for Fitness Freaks

Update on Sept. 13, 2025, 7:41 a.m.

I bought a pair of noise-cancelling earbuds for the price of a sandwich to find out. It taught me the most important lesson in technology: there are no miracles, only trade-offs.

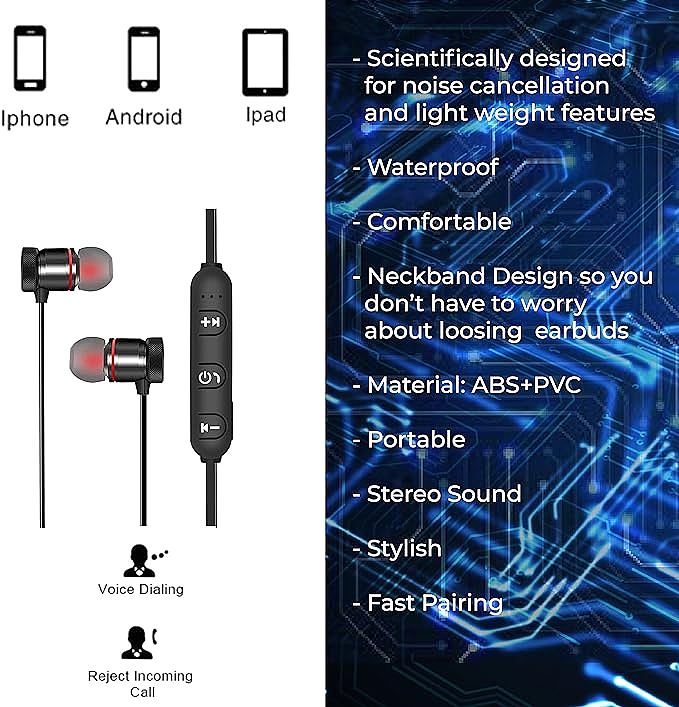

It was the price that first caught my eye: $11.99. For that, the online listing for the “Hypertech X EP1 Neckband Bluetooth Headphones” promised a buffet of modern tech marvels: quick-pairing Bluetooth, a waterproof design for sports, and the holy grail itself—noise cancellation. For less than the cost of a movie ticket, it offered a ticket to personal auditory bliss.

Then, I scrolled down to the reviews and found a perfect paradox. The four people who had rated it were split down the middle, a statistical schism of 48% five-star raves and 52% one-star rants. One user called it a “Great Value.” Another, with palpable frustration, wrote, “Very cheap. Sound not that good. Can’t go to far away from phone loses signal.”

How could one piece of technology be both a triumph and a failure? The answer, I realized, wasn’t in the device itself, but in the invisible compromises baked into its very existence. So, I ordered one. Not to review it, but to perform a conceptual autopsy. This little gadget, I suspected, was a masterclass in a discipline that defines every piece of technology you own: the science of value engineering. This isn’t its story; it’s the story of the physics it had to bend to meet that impossible price.

The Physics of Manufactured Silence

Let’s start with the most audacious claim: noise cancellation. At its heart, Active Noise Cancellation (ANC) is a thing of physics-bending beauty. It operates on a principle called destructive wave interference.

Imagine sound waves as ripples in a pond. The steady hum of an airplane engine is a series of uniform, rolling ripples. ANC works by using tiny microphones to “listen” to these incoming ripples. It then instantaneously generates a new set of “anti-ripples” that are a perfect mirror image—where the original ripple has a crest, the anti-ripple has a trough. When they meet in your ear canal, they cancel each other out. The pond, in theory, becomes still. Silence.

To do this well is astonishingly complex. High-end headphones from brands like Sony or Bose use multiple microphones inside and outside the ear cup, coupled with powerful Digital Signal Processors (DSPs) running sophisticated algorithms to analyze and counteract a wide range of noises in real-time. It’s a computational symphony.

So how does an $11 device attempt this symphony with what is likely a kazoo? It makes a critical compromise. We can infer from the price point that the EP1 likely uses a very basic, “feed-forward” ANC system. This involves a single external microphone and a simple circuit designed to target a very specific and predictable type of sound: low-frequency, constant noise.

This is the key. It’s engineered not to cancel all noise, but only the easiest noise.

It’s designed to fight the monotonous hum of a server room fan, the drone of a bus engine, or the whir of an office HVAC system. It is almost certainly ineffective against the kind of sounds that bother us most: a coworker’s phone call, a barking dog, or the clatter of a coffee shop. These sounds are too complex, too sudden, and too high-frequency for a simple ANC circuit to handle.

This single engineering trade-off perfectly explains the split reviews. The user who found it a “Great Value” might be using it to drown out the low hum of their office air conditioner, a task for which it is adequately designed. The user who found it “Very cheap” might have hoped it would silence their noisy commute, a task for which it is woefully unequipped. The feature isn’t broken; it’s just a very specific, cost-effective sliver of the real thing.

The Invisible Leash of Bluetooth

Next, let’s untangle the mystery of its wireless connection. The convenience of Bluetooth feels like magic, but its origins are even more fascinating. The core technology, known as frequency-hopping spread spectrum, was co-invented during World War II by Hollywood actress Hedy Lamarr to guide torpedoes without being jammed. Today, that same principle lets you listen to podcasts while your phone is in your pocket.

Yet again, the user reviews present a contradiction. One claims the “Bluetooth range is adequate,” while another complains they “Can’t go to far away from phone loses signal.” Both are likely telling the truth.

Bluetooth operates in the crowded 2.4 GHz radio band, the same public space used by Wi-Fi, microwave ovens, and a dozen other wireless devices. It’s less like a private conversation and more like trying to talk to a friend across a loud, crowded party.

The stability of that connection depends on a few factors, all of which are subject to cost-cutting:

1. The Antenna: A well-designed antenna is crucial for sending and receiving a clear signal. In a device this small and cheap, the antenna is likely a tiny, compromised trace on the circuit board, not a high-performance component.

2. The Chipset: More expensive Bluetooth chips have better signal processing to filter out interference and maintain a connection. The module in the EP1 is almost certainly a budget-friendly, off-the-shelf solution that prioritizes cost over signal robustness.

3. The Physics of You: The 2.4 GHz signal is notoriously bad at traveling through water. Since the human body is mostly water, simply putting your phone in your back pocket and turning your head can be enough to block the signal to your headphones.

The user with the “adequate” range might be sitting at a desk with their phone right in front of them in a radio-quiet environment. The user with the signal loss might be trying to use it at the gym, their body constantly moving and blocking the signal, in a room flooded with other people’s Wi-Fi and Bluetooth signals.

But there’s an even deeper compromise at play here that explains the “Sound not that good” comment. Before audio is sent over Bluetooth, it must be compressed by a program called a codec. The most basic, universally required codec is the Sub-Band Codec (SBC). It’s old, it’s free to use, but its compression algorithm is notoriously “lossy,” meaning it throws away audio data to save space, often resulting in a flatter, less detailed sound. High-end headphones support superior codecs like aptX or LDAC, which require licensing fees and more powerful hardware. The EP1, to meet its price, almost certainly uses SBC and nothing more. It’s an audible trade-off, made before a single note even reaches the headphones’ tiny speakers.

The Science of “Plasticky”

Finally, let’s consider the physical object itself. The product description boasts of a construction from “durable ABS+PVC materials.” This isn’t just a random string of acronyms; it’s a deliberate engineering choice that speaks volumes about its design philosophy.

Not all plastics are the same. This combination is a classic pairing in consumer electronics for balancing cost and function. * ABS (Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene) is likely used for the hard shells of the earbuds themselves. It’s the same stuff LEGO bricks are made from. It’s rigid, tough, impact-resistant, and incredibly cheap to injection-mold into complex shapes. It provides the necessary protection for the delicate electronics inside. * PVC (Polyvinyl Chloride) is probably used for the flexible neckband and the thin wires. It’s durable, flexible, and provides good electrical insulation. It can withstand being bent and twisted repeatedly.

Together, they create a product that is lightweight (just 0.317 ounces) and durable enough for daily use, all for pennies on the dollar. The description also claims it’s “Waterproof.” This is perhaps the most common marketing compromise of all. Without a specific IP (Ingress Protection) rating, “waterproof” is functionally meaningless. Given the materials and intended use for sports, we can infer it likely meets an IPX4 standard. This means it can resist splashing water from any direction—in other words, it’s sweat-proof and rain-proof. You can jog with it, but don’t you dare drop it in a pool. It’s another calculated decision: providing just enough protection for the most common use case, without incurring the cost of true, submersible waterproofing.

The Gospel of Good Enough

After spending time with the Hypertech X EP1, I didn’t come away with a verdict on whether it’s a good or bad product. I came away with a profound appreciation for the engineering art of the “good enough.”

This $11.99 device is a physical manifestation of countless trade-offs. Its noise cancellation is a sliver of the real thing, its Bluetooth connection is a negotiation with physics, and its materials are a masterclass in cost-effective durability. At every step of its design, a conscious decision was made to sacrifice a degree of performance to shave another fraction of a cent off the final cost.

It teaches us that modern technology isn’t about magic. It’s about a series of deliberate, calculated compromises. The Hypertech X EP1 isn’t a miracle; it’s a testament to the fact that in engineering, you get exactly what you pay for. And in understanding that, you gain a new lens through which to see every piece of technology in your life. The next time you see a gadget that seems too good to be true, you’ll know what to look for: not the features it proudly lists, but the invisible, ingenious, and necessary compromises it made to exist at all.