Sony MDR-AS210/B Sport Headphones: Stay in the Groove, Stay Secure

Update on Sept. 22, 2025, 10:41 a.m.

The rhythm is perfect. Each beat of the synth drum in your ears lands in perfect sync with your feet hitting the pavement. The city around you—a symphony of roaring buses, distant sirens, and chattering crowds—fades into a muted, irrelevant hum. You are in the zone, a world of pure audio-fueled motivation. Then, a sudden, violent blast of a car horn from inches away shatters your cocoon. You leap back, heart hammering, adrenaline surging. You were so lost in the music, you never even heard the car approaching.

This heart-stopping moment, familiar to any urban runner, cyclist, or pedestrian, reveals a dangerous paradox of modern audio technology. In our relentless pursuit of sonic perfection, immersive bass, and absolute silence from the outside world, are we inadvertently engineering away one of our most crucial survival instincts? Have we become so obsessed with what we want to hear that we’ve forgotten what we need to hear?

The answer lies not in the specifications of our gadgets, but deep within the intricate wiring of our own brains. And sometimes, the most profound lessons come from the most unassuming pieces of technology—in this case, a simple pair of sport headphones that chooses to cooperate with our biology rather than conquer it.

The Allure of the Sonic Cocoon

Before we understand why letting the world in is so important, we must first appreciate the seductive physics of keeping it out. Most popular earbuds and headphones today are marvels of acoustic isolation. They achieve this in two ways: passively, by using silicone tips to create an airtight seal in your ear canal, and actively, with noise-cancellation technology that uses microphones to create “anti-noise” waves, erasing ambient sounds.

This sealed environment does wonders for music. It creates a closed chamber where bass frequencies, which are simply slow-moving waves of air pressure, can build up and resonate. This is a practical application of Helmholtz Resonance—the same principle that makes a sound when you blow across the top of a bottle. Without this sealed cavity, bass dissipates, sounding thin and weak. This is why audiophiles cherish the deep, rich sound of closed-back headphones.

But this perfect sonic cocoon is an illusion. It’s a sensory deprivation chamber for our most vigilant sense. By blocking the subtle, ever-present soundscape of our environment, we are unplugging a sophisticated biological supercomputer that has been fine-tuned by millions of years of evolution to keep us alive.

Your Brain’s Superpower, Unplugged

Long before we had playlists, our hearing was a primary tool for survival. It allowed us to detect a predator in the rustling grass or the crack of a twig behind us. To do this, our brain developed an astonishing set of abilities, a field of study known as psychoacoustics.

One of its most remarkable tricks is the “Cocktail Party Effect.” First described by psychologist Colin Cherry in the 1950s, this is your brain’s uncanny ability to focus on a single voice in a room full of chatter, effectively filtering out all other conversations. It’s a selective attention mechanism that allows us to find signal in the noise. When you wear noise-cancelling headphones, you aren’t letting your brain do its masterful filtering work; you’re just turning off the noise entirely, signal and all.

Even more critical is our brain’s built-in GPS: our ability to locate sound in three-dimensional space. This isn’t magic; it’s physics, processed with breathtaking speed. Our brain relies on binaural cues, specifically:

- Interaural Time Difference (ITD): A sound coming from your right will reach your right ear a few microseconds before it reaches your left.

- Interaural Level Difference (ILD): That same sound will be slightly louder in your right ear than your left, as your head creates an “acoustic shadow.”

Your brain instantly computes these minuscule differences to paint a precise map of your surroundings. A sealed earbud disrupts this delicate system. It pipes identical, pre-mixed stereo sound directly into your ear canals, bypassing the natural way your outer ears—the pinnae—are shaped to capture and funnel directional sound. You can hear the music, but you lose your sense of where.

A Lesson in Humble Design

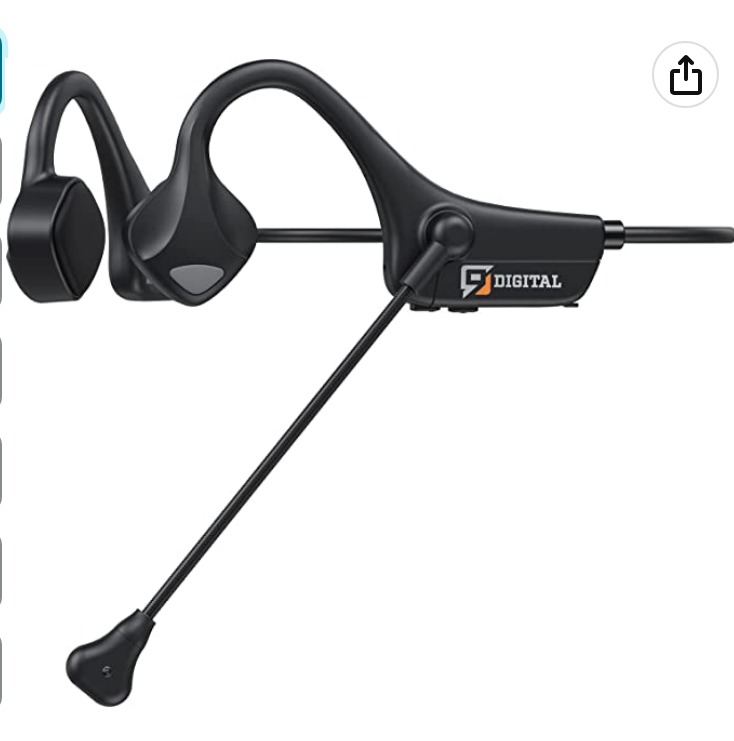

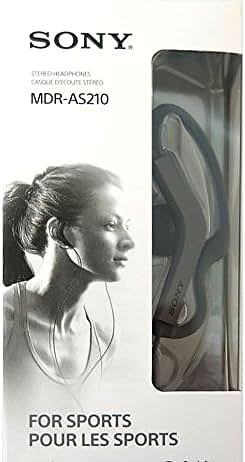

This is where our unassuming case study, the Sony MDR-AS210/B Sport Headphones, enters the frame. Released in an era already dominated by the push towards wireless and noise-isolating buds, this simple, wired headphone represents a radically different design philosophy. It is not a technological marvel, but a biological one.

Its most important feature is what it lacks: a seal. The design is “acoustically open.” The earpieces rest gently in the outer ear, allowing outside sound to mix freely with the music. To a bass-head, this is a fatal flaw; as we learned from Helmholtz, the lack of a sealed chamber means the bass response is inherently weak. But from a survival standpoint, this is its genius. It allows your brain’s “Cocktail Party” filter and sound-localization GPS to remain fully operational. You get your motivational soundtrack, but your brain still gets the raw data it needs to keep you safe.

Furthermore, its physical design—an adjustable loop hanger that gently hooks over the ear—is a lesson in biomechanics. It doesn’t rely on jamming itself into the ear canal. Instead, it uses the rigid structure of the pinna as a stable anchor. This not only keeps it secure during vigorous workouts but also minimizes interference with the pinna’s natural, crucial role in shaping incoming sound waves to help you determine a sound’s elevation. The design doesn’t fight your anatomy; it collaborates with it.

Redefining Fidelity

For decades, we’ve defined “high-fidelity” audio as the perfect, uncolored reproduction of a recording. We’ve strived to eliminate the room, the noise, the world itself, to get closer to the “pure” sound. But for anyone moving through that world, this definition is dangerously incomplete.

Perhaps true fidelity isn’t just about reproducing music with perfect clarity. Perhaps, for an active listener, true high-fidelity is about faithfully representing the entire auditory reality of a given moment—the music, yes, but also the approaching footsteps, the distant rumble of thunder, the whir of a bicycle’s tires on wet pavement.

The simple, open-backed sport headphone is a quiet reminder of this forgotten truth. It concedes that its reproduction of the music will be imperfect, compromised by the sounds of life. But in doing so, it allows for a more profound, more honest, and infinitely safer listening experience. It suggests that sometimes, the most advanced technology is not the one that creates the most convincing illusion, but the one that allows us to remain most connected to reality. The next time you choose your headphones, the question shouldn’t just be “How good do they sound?” but “How well do they let me listen?”