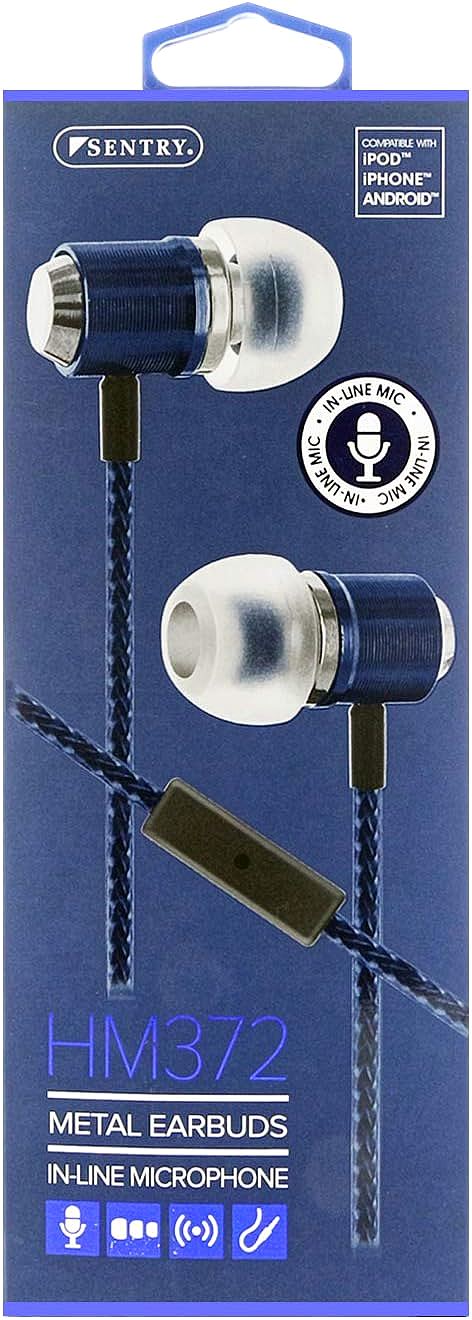

Sentry Industries HM372 MicBuds Metal Stereo Ear Buds With Built-In Mic - Ideal for Music and Calls

Update on June 6, 2025, 4:57 p.m.

It’s a scenario familiar to many of us. Your treasured, expensive wireless earbuds are dead, lost, or forgotten at home. You’re facing a long commute, a noisy flight, or a crucial phone call, and silence is not an option. You dash into a drugstore or airport kiosk and grab what’s available: a blister-packed pair of wired earbuds, likely costing less than your lunch. The expectation is low. You just need them to work. But then, you plug them in, press play, and a funny thing happens. The sound isn’t just present; it’s… surprisingly decent. The bass has a punch you didn’t anticipate. You’ve just experienced a tiny, ten-dollar miracle.

This isn’t a miracle, of course. It’s physics. It’s a quiet testament to a century of audio engineering, distilled into a product so cheap we treat it as disposable. Let’s take one such example, the Sentry Industries HM372, and instead of reviewing it, let’s dissect it. Let’s put on our architect’s hat and our engineer’s coat to tour the surprisingly sophisticated concert hall that fits in your pocket.

Building the Venue: An Introduction to Your Personal Concert Hall

Think of every earbud not as a piece of plastic, but as a miniature, custom-built concert hall for an audience of one. The quality of your listening experience depends entirely on the design of this tiny venue. How good is the orchestra? What are the walls made of? And most importantly, what clever architectural tricks have been used to shape the sound? Our tour of this particular $10 venue will reveal that even on a shoestring budget, the laws of physics can be a powerful and reliable ally.

The Orchestra in Your Palm: The 8mm Driver

At the heart of our concert hall is the orchestra—the component that actually makes the music. In the HM372, this is an 8-millimeter dynamic driver. Don’t let the term intimidate you. A dynamic driver works on a principle that is both elegant and simple, much like a tiny, high-tech drum.

Inside, a voice coil attached to a diaphragm (the “drum skin”) receives electrical signals from your phone. A magnet creates a field around this coil. As the electrical signal fluctuates with the rhythm and pitch of the music, it causes the coil and the attached diaphragm to vibrate rapidly back and forth. This vibration pushes and pulls the air, creating the sound waves that your ear perceives as music. The driver is, quite literally, the entire orchestra in your palm.

The specifications tell us this orchestra has an impressive range, a frequency response of 20Hz to 20KHz. This covers the full, internationally recognized spectrum of human hearing—from the deep, subsonic rumble of a bass synthesizer (20Hz) to the shimmering, airy sizzle of a cymbal (20KHz). Its low impedance of 16 ohms simply means it doesn’t require much power to perform, making it a perfect match for the modest output of a smartphone. But a wide range alone doesn’t guarantee a good performance. The magic is in how the venue shapes the sound.

The Architecture of Bass: A Lesson from Ancient Flutes

Here is where our tour gets fascinating. The most common complaint about cheap earbuds is thin, lifeless sound, utterly lacking in bass. To combat this, budget-conscious engineers can’t just throw in a bigger driver. Instead, they must become clever architects of air. The HM372 boasts an “acoustic sub-woofer chamber,” a feature that relies on a beautiful principle of physics discovered in the 1850s by a German physician and physicist named Hermann von Helmholtz.

It’s called Helmholtz Resonance.

You’ve experienced it yourself. When you blow across the top of a glass bottle, you create a low, pure tone. The pitch of that tone is determined by the volume of air inside the bottle (the chamber) and the size of the opening. The chamber acts as a resonator, naturally amplifying sound waves at a specific low frequency.

The earbud’s acoustic chamber is a precisely shaped cavity behind the driver that does the exact same thing. It’s engineered to resonate at the lower end of the audio spectrum. When the driver produces sound, the air within this tiny chamber vibrates in sympathy, amplifying the bass frequencies just as a guitar’s body amplifies the sound of its strings. It’s a purely physical, passive way to create a richer, fuller low-end—a trick borrowed from ancient flutes and ocarinas to give a ten-dollar earbud a satisfying thump. It’s not an electronic boost; it’s architecture.

The Building Materials: Why Metal Matters

Our concert hall’s performance also depends on what it’s made of. Many cheap earbuds are housed in flimsy plastic, which can feel brittle and, more importantly, can vibrate along with the music, coloring and muddying the sound. It’s like listening to a concert in a hall with rattling walls.

The HM372’s use of a metal housing is a decision rooted in both durability and acoustics. The first benefit is obvious and confirmed by real-world testimony. One user reported their earbuds survived being vacuumed up by a robotic cleaner—not once, but eight times. This is the kind of resilience that brittle plastic simply cannot offer.

The second benefit is subtler. A rigid, dense material like metal provides better acoustic damping. It resists vibrating on its own, providing an inert, stable enclosure for the driver to do its work. This prevents unwanted resonances from interfering with the sound, leading to a cleaner, more precise audio reproduction. The metal isn’t just for show; it’s the solid foundation of our concert hall, ensuring the music we hear is the music the orchestra intended to play.

The Last Analog Wire: An Ode to the 3.5mm Jack

Finally, our tour must acknowledge the elegant, aging entryway to our concert hall: the 3.5mm headphone jack. In our modern era of wireless everything, the wired connection can seem archaic. But it holds a quiet, profound reliability. There are no batteries to die, no pairing protocols to fail, no audio-video lag when watching a movie. Its history stretches back to the 19th-century telephone switchboards, and its simple design—a Tip, a Ring, and a Sleeve (TRS) to carry the left, right, and ground signals—is a marvel of robust, universal engineering. For a product built on a budget, this dependable, license-free connection is the most logical choice, a direct, uninterrupted physical path from the artist to your ears.

Encore: The Unsung Engineering

By the end of our tour, it becomes clear that we are not holding a mere disposable product. The Sentry HM372, like many objects of its class, is a vessel of applied science. It tells a story of compromise and ingenuity, where engineers, bound by extreme cost constraints, turn to the fundamental laws of physics to achieve their goals.

We don’t need to declare it the best earbud in the world. That was never the point. The true value lies in seeing it for what it is: a pocket-sized concert hall, cleverly designed. It features a capable orchestra, an acoustically-tuned chamber inspired by 19th-century physics, and a structure built with robust materials. It’s a reminder that even in the most mundane corners of our technological world, there is a quiet, unsung symphony of engineering at play, waiting to be heard.