Bluetooth 4.1 in the Modern Era: Deconstructing the RLX Wireless Headphone Architecture

Update on Nov. 23, 2025, 5:09 p.m.

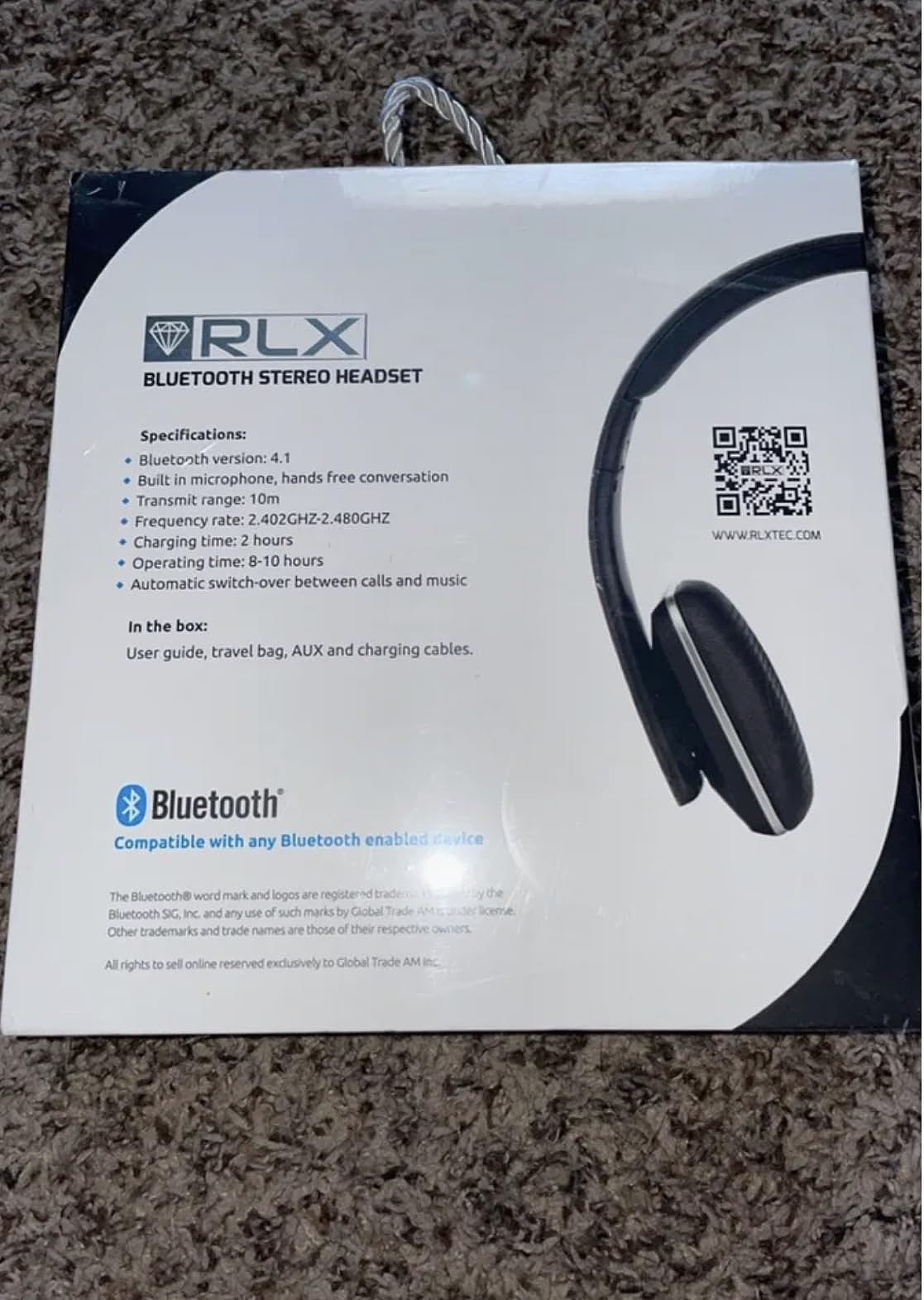

In the relentless march of consumer electronics, specificity is often lost in marketing. We are bombarded with version numbers and acronyms, rarely stopping to understand what they imply for the user experience. The RLX Wireless Bluetooth Headphone (Model RLX-100) serves as a fascinating case study in this technological timeline.

Often encountered in retail kiosks or bundled deals, this device operates on Bluetooth 4.1, a standard that, while superseded, offers a distinct window into the evolution of wireless audio. By dissecting its specifications—from its communication protocols to its power management—we can better understand the trade-offs and engineering decisions that define “legacy” tech in a modern world.

The Protocol Breakdown: Bluetooth 4.1 vs. The World

To understand the performance of the RLX-100, one must first decode its transmission standard. Bluetooth 4.1, released in 2013, was a pivotal update focused on the “Internet of Things” (IoT), but its implications for audio are specific.

Unlike the modern Bluetooth 5.x standards which prioritize massive data throughput and range, Bluetooth 4.1 focused on Coexistence. * LTE Coordination: Its primary engineering achievement was reducing interference with 4G LTE signals. For a headphone user, this means that despite being an older protocol, the connection remains relatively stable even when your phone is actively pulling heavy data usage nearby. * Smart Connectivity: It introduced better reconnection intervals. If you step out of the advertised 10-meter range and return, the device attempts to reconnect automatically—a feature we now take for granted but was a significant engineering hurdle at the time.

However, users should be aware of the limitations. Bluetooth 4.1 does not support the higher bandwidth required for lossless codecs like LDAC or aptX HD. The audio transmission relies on the standard SBC codec, which compresses audio data. For casual listening, this is sufficient, but audiophiles will note the difference in dynamic range compared to wired connections.

The Metadata Anomaly: “In-Ear” vs. “Over-Ear”

A curious aspect of the RLX-100’s digital footprint is the listing description “Form Factor: In Ear.” This is a classic example of Metadata Taxonomy Error in e-commerce.

As evidenced by the physical weight (14.4 ounces) and the visual design, this is unequivocally a Supra-aural (On-Ear) or Circumaural (Over-Ear) device, depending on the user’s ear size. * The Physics of Isolation: Unlike in-ear monitors that seal the ear canal, the RLX-100 relies on the clamping force of the headband and the density of the ear cushions to create a seal against the skull. This creates Passive Noise Isolation. * Acoustic Leakage: Because it sits on or over the ear, the seal is less absolute than an earplug. This design typically allows for a wider “soundstage” (the perceived spatial location of sound) but requires higher volume levels to compete with ambient noise compared to in-ear models.

Power Dynamics: 500mAh in Perspective

The device houses a 500mAh Lithium-ion battery. In the context of modern headphones, is this large or small?

- Energy Density vs. Consumption: Modern flagship headphones often carry 700-1000mAh batteries. However, older Bluetooth 4.1 chipsets are less power-efficient than their 5.0 counterparts. This explains the rated 8-10 hours of playback.

- The Charge Cycle: The 2-hour charging time via Micro-USB (DC 5V) indicates a standard charging rate of roughly 0.5C. While it lacks the “Fast Charge” capabilities of USB-C PD devices (which can give hours of play in minutes), this slower charging rate is actually beneficial for the long-term health of the lithium cells, reducing thermal stress during the charge cycle.

The Hybrid Advantage: Wired Redundancy

One feature that redeems many limitations of older wireless tech is the inclusion of a 3.5mm AUX input.

From an engineering standpoint, this jack bypasses the internal DAC (Digital-to-Analog Converter) and amplifier.

1. Zero Latency: When gaming or editing video, Bluetooth 4.1 can introduce latency (audio lag) of over 150ms. Plugging in a cable reduces this to zero—limited only by the speed of electrons in copper.

2. Infinite Runtime: It transforms an active electronic device into a passive acoustic transducer. When the 500mAh battery is depleted, the device doesn’t become a paperweight; it becomes a standard wired headphone. This redundancy is a crucial feature for travelers who cannot guarantee access to charging ports.

The “Touch” Interface: Capacitive vs. Physical

The RLX-100 utilizes a touch-control interface on the ear cup. In consumer electronics, switching from physical buttons to capacitive touch reduces mechanical failure points (buttons can’t wear out if they don’t exist).

However, this introduces the challenge of Haptic Ambiguity. Without the physical “click” of a button, users must rely on audio cues or muscle memory to know if a command (like skipping a track) was registered. For a device often used during “Sports and Exercise,” where sweaty hands or movement can interfere with capacitive sensors, this design choice prioritizes aesthetics over tactile precision.

Conclusion: Understanding the Tool

The RLX Wireless Bluetooth Headphone is a product of its time, encapsulated in a modern shell. It does not compete with the high-fidelity codecs or active noise cancellation of current flagship models. Instead, it offers a functional, utilitarian approach to audio. By understanding the capabilities of Bluetooth 4.1 and the physics of its design, users can temper their expectations and utilize the device for what it is: a robust, hybrid listening tool that bridges the gap between the wired past and the wireless present.