ABRAMTEK E8: Tiny Earbuds, Big Sound for Small Ears

Update on July 24, 2025, 11:41 a.m.

There’s a unique magic to it. With the press of a button or the simple act of placing two tiny objects in your ears, the clamor of the world recedes, replaced by an intimate soundscape built just for you. A favorite song can feel like a whispered secret, a driving beat can become your own personal pulse, and a podcast host can sound like they’re sitting right beside you. This experience, so commonplace today, is the culmination of a century-long journey, a relentless quest to solve a deceptively complex problem: how do you perfectly bridge the gap between a recording and the human soul?

The answer isn’t just in the plastic and wires you hold in your hand. It’s a story woven from kitchen-table ingenuity, profound scientific discoveries about our own senses, and meticulous engineering that tackles the very physics of sound and comfort. This is the story of how we put a symphony in our pocket.

The Spark in the Kitchen

Our journey begins not in a sterile Silicon Valley lab, but in the cluttered kitchen of an inventor named Nathaniel Baldwin in 1910. An electrical engineer and a devout follower of the Mormon faith, he struggled to hear the sermons in his local tabernacle. Driven by necessity, he tinkered with receivers, wire, and a headband, crafting a device that could amplify sound and deliver it directly to his ears. His invention, crude by today’s standards, was revolutionary. He had created one of the first practical sets of headphones.

He offered his invention to the U.S. Navy, who, after initial skepticism, ordered 100 units. Baldwin, working from his kitchen, fulfilled the order and unknowingly ignited the age of personal audio. For decades, however, headphones remained the domain of professionals—radio operators, pilots, and sound engineers. They were heavy, uncomfortable, and utilitarian. The idea of them as a consumer product for pleasure was almost unthinkable until 1958, when John C. Koss introduced the Koss SP/3, the first commercial stereo headphones. Suddenly, music lovers could immerse themselves in the wide, new world of stereophonic sound. The quest had begun, but it immediately ran into its first, and perhaps most enduring, obstacle: the human ear itself.

The Ghost in the Machine

To create the perfect listening device, engineers had to realize they weren’t just designing for the ear; they were designing for the brain. This is the realm of psychoacoustics, the fascinating science that studies the relationship between physical sounds and our psychological perception of them. What we think we hear is an intricate interpretation, a story our brain tells itself based on the data it receives.

One of the most critical elements in this story is the “acoustic seal.” When an earbud fits snugly within your ear canal, it does more than just block outside noise. It creates a tiny, closed chamber. This seal is paramount for reproducing low-frequency sounds. Bass notes are long, powerful waves that require a contained space to build pressure and be perceived correctly. A poor fit is like leaving a window open in a concert hall; all the foundational richness of the sound escapes, leaving you with a thin, tinny audio profile.

But even with a perfect seal, our hearing is not a perfect microphone. As research by pioneers like Harvey Fletcher and Wilden A. Munson revealed in the 1930s, human hearing sensitivity varies dramatically with frequency and loudness. Our ears are exquisitely tuned to the frequencies of human speech, but are far less sensitive to very low and very high tones, especially at lower volumes. This is why the pursuit of a “balanced sound” is so complex. A truly high-fidelity earphone doesn’t just reproduce every frequency with equal force; it aims to deliver them in a way that sounds natural and complete to the human ear, compensating for our innate perceptual biases. It’s an engineering solution to a biological quirk.

The Modern Marvel

Flash forward to today. The challenge is no longer just about creating stereo sound, but about delivering it in a package that is nearly invisible, profoundly comfortable, and durable enough to survive the rigors of modern life. The journey from a bulky headset tethered to a record player to a pair of true wireless earbuds is a masterclass in miniaturization and material science.

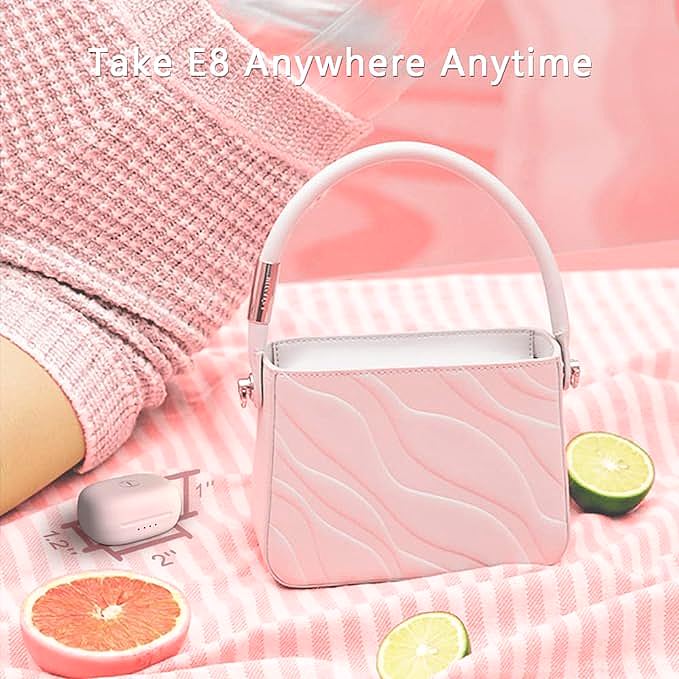

Here, we can look at a contemporary device like the ABRAMTEK E8 Small Wireless Earbuds not as an advertisement, but as a tangible collection of solutions to these century-old problems.

The ghost of Nathaniel Baldwin’s heavy, uncomfortable headset is banished by a relentless focus on ergonomics. Each earbud weighs a mere 3.6 grams. This isn’t just a number; it’s a victory over physics. The minimal mass dramatically reduces the pressure on the ear’s sensitive cartilage, making hours of listening feel effortless. The construction from Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS) provides a lightweight yet robust shell, a material chosen for its ability to withstand impact without adding bulk. Most importantly, the inclusion of differently sized eartips directly addresses the acoustic seal problem, allowing a user to find a personalized fit that unlocks the true bass response and isolates them from the outside world.

The problem of fragility in an active world is met with standardized engineering. The IPX7 rating, for instance, is not a marketing slogan but a precise benchmark from the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC 60529). It certifies that the device can withstand being submerged in one meter of water for thirty minutes. This ensures that the delicate electronics are protected from a sudden downpour or the corrosive nature of sweat—a durability unthinkable in the early days of personal audio.

The Sound of Tomorrow in Your Ears Today

From a kitchen invention born of a need to hear a sermon, to a global cultural phenomenon defined by the white cables of an iPod, the headphone has been on an incredible journey. That journey has always been about more than just technology; it’s been about our relationship with sound, with music, and with ourselves. The goal was never merely to make the devices smaller, but to make the experience bigger, more immersive, and more seamlessly integrated into the fabric of our lives.

So the next time you place those tiny marvels in your ears and the world melts away, take a moment. You are not just listening to a song. You are wearing a piece of history, a pocket-sized testament to human ingenuity, and the beautiful, century-long effort to capture a ghost in a machine.