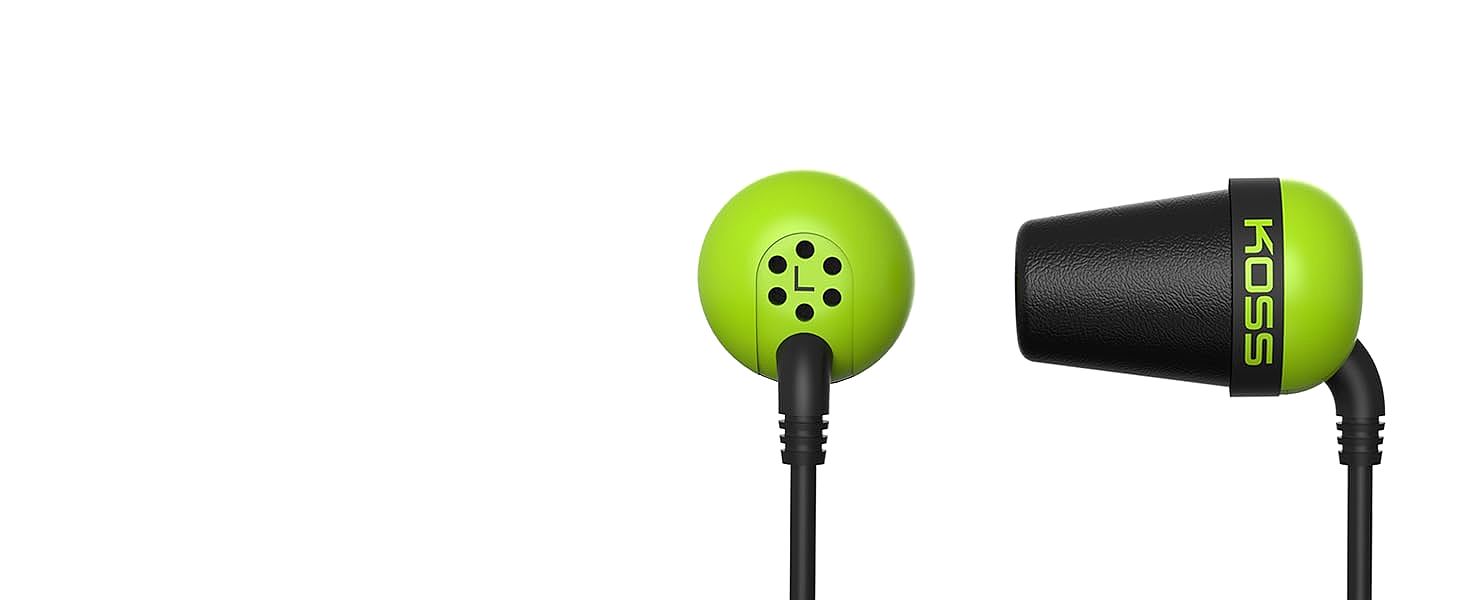

Koss The Plug In-Ear Headphones: Superior Sound Isolation and Comfort

Update on Aug. 24, 2025, 5:18 p.m.

We live in a world saturated with sound. It is the inescapable soundtrack to modern life—the low-frequency rumble of a subway car, the layered chatter of a busy office, the distant drone of traffic. In this constant acoustic barrage, we often seek refuge. We crave a personal sanctuary, a bubble of quiet where we can focus, relax, or simply lose ourselves in music. The modern market offers a dazzling array of technological solutions, often involving complex algorithms and battery-powered circuitry. Yet, one of the most effective and elegant solutions comes not from cutting-edge electronics, but from a deep understanding of fundamental physics, embodied in a deceptively simple device: the Koss The Plug.

To understand The Plug is to appreciate a legacy. In 1958, John C. Koss didn’t just create a product; he launched a revolution. His SP/3 Stereophones were the world’s first, and they single-handedly created the category of personal listening, transforming music from a public, room-filling experience into an intimate, personal one. Decades later, The Plug carries this legacy forward, not with more complexity, but with a radical focus on the essentials. It is a masterclass in how clever design, rooted in science, can outperform brute force. Our journey is to peel back its humble exterior and discover the powerful principles of material science, acoustics, and human perception that make it work.

The Science of the Seal: A Microscopic Labyrinth for Sound

The magic of The Plug, and the core of its acoustic power, lies in its most prominent feature: the colorful, pliable foam tips. These are not merely soft pads for comfort; they are precision-engineered acoustic tools. The material is known as viscoelastic polyurethane foam, or more famously, memory foam. Its origins trace back to a NASA contract in the 1960s to improve aircraft seat cushioning, and its unique properties make it perfectly suited for sound isolation.

The term “viscoelastic” describes its dual nature: it exhibits properties of both a viscous fluid (it flows and deforms under pressure) and an elastic solid (it returns to its original shape). When you compress the foam tip and insert it into your ear, it doesn’t just spring back. It expands slowly, meticulously conforming to every unique contour of your ear canal. This creates a near-perfect, custom anatomical seal that is the foundation of passive noise isolation—the physical act of blocking sound.

But the process goes deeper than just plugging a hole. On a microscopic level, the foam is an open-cell structure, a complex, three-dimensional labyrinth of interconnected pockets. When external sound waves—which are simply vibrations traveling through the air—strike the foam, they are forced into this maze. As the air molecules vibrate within these tiny, tortuous passages, friction converts their kinetic energy (the sound) into an infinitesimal amount of heat. The sound wave doesn’t just bounce off; it gets trapped, dampened, and effectively neutralized. This is why foam is a far superior sound absorber than a solid, non-porous material like silicone, which primarily reflects sound and is less adaptable to the ear’s shape. The Plug’s foam tip is, in essence, a silent, microscopic fortress built at the gateway to your ear.

The Engine of Sound: Painting with Air Pressure

With the outside world effectively silenced, the stage is set for the headphones to create their own. Inside each earpiece lies the heart of the system: a dynamic driver. The principle is beautifully straightforward and has been the workhorse of audio for a century. Think of it as a miniature piston, or a tiny, high-speed loudspeaker. An electrical audio signal from your phone or music player flows into a finely wound voice coil attached to a thin, lightweight membrane called a diaphragm. This coil is suspended in a magnetic field created by a permanent magnet.

As the electrical current of your music fluctuates, it generates a changing magnetic field around the coil. This new field interacts with the permanent magnet’s field, causing the coil—and the attached diaphragm—to vibrate back and forth with incredible speed and precision. These vibrations push and pull on the air molecules in the sealed space of your ear canal, creating pressure waves that your brain interprets as sound. The deep thrum of a bass guitar is a slow, powerful push; the shimmer of a cymbal is a rapid, delicate flutter.

The specifications tell a story of intentional design. An impedance of 16 Ohms is considered low, meaning the driver requires very little power to move. This is a deliberate choice, ensuring that even a low-voltage device like a smartphone can easily drive the headphones to a satisfying volume without the need for an external amplifier. The wide frequency response of 10 to 20,000 Hz signals an ambition to reproduce the entire spectrum of audible sound, from sub-bass rumbles you feel more than hear (below 20 Hz) to the highest treble details.

One might notice a tiny, strategically placed hole on the housing—an acoustical vent. This may seem counter-intuitive for a device designed to seal out sound. However, this is not a flaw; it is a crucial piece of acoustic tuning. In a completely sealed chamber, the driver’s movement could create uncomfortable air pressure. The vent acts as a controlled leak, relieving this pressure. More importantly, it allows engineers to precisely shape the sound, particularly the bass response. By controlling the airflow behind the driver, they can prevent the low frequencies from becoming boomy or muddy, resulting in a cleaner, more controlled sound. It is a subtle but vital touch of engineering finesse.

The Listener’s Brain: Why Quiet Sounds Better

The true brilliance of The Plug’s design is revealed not just in physics, but in psychoacoustics—the study of how our brain perceives sound. The most significant benefit of its superior noise isolation is how it combats a phenomenon known as the auditory masking effect.

Imagine trying to hear a whispered conversation in a room with a loud air conditioner running. The whisper is still technically there, but the louder, broader sound of the AC unit effectively drowns it out, “masking” it from your perception. This happens constantly with music. The low-frequency rumble of a bus engine can completely obscure the subtle notes of a cello. The high-frequency hiss of an airplane cabin can erase the delicate decay of a cymbal.

By creating a quiet background, The Plug dramatically reduces this masking effect. Suddenly, the quieter, more nuanced parts of a recording are unveiled. The intricate fingerwork on an acoustic guitar, the soft intake of a singer’s breath, the distant echo in a concert hall—details that were previously lost in the environmental noise are now clear and present. The consequence is profound: you can achieve a richer, more detailed listening experience at a significantly lower, and therefore safer, volume. You don’t need to crank up the music to overcome the noise; you simply remove the noise. This directly relates to the Fletcher-Munson curves, which describe how our hearing is less sensitive to low and high frequencies at lower volumes. By preserving a quiet canvas, The Plug allows the full frequency spectrum of the music to shine through, even at moderate levels.

The Art of the Possible: Engineering in a World of Compromise

No design exists in a vacuum. Every product is a series of decisions and compromises, a delicate balance between performance, cost, and longevity. To ignore the real-world limitations of The Plug would be to miss the final, crucial lesson in its design. User feedback consistently highlights a primary concern: durability. After months or years of use, a connection may loosen, or a wire may fray.

This is not necessarily a sign of poor design, but rather a transparent reflection of a design trade-off. To deliver its remarkable acoustic performance at such an accessible price point, compromises must be made. These often occur in the materials and construction of components that are under constant mechanical stress—the cable, the Y-splitter, and particularly the 3.5mm jack that is repeatedly plugged, unplugged, and bent in a pocket. Using more robust, over-engineered components would inevitably raise the cost, shifting the product into a different category entirely. The Plug’s engineering prioritizes the elements critical to its acoustic mission—the foam and the drivers—while accepting a more limited lifespan for its structural components.

Similarly, the matter of comfort is a lesson in the beautiful, frustrating diversity of human anatomy. For many, the expanding foam creates a secure, comfortable fit that is ideal for active use. For others, particularly those with smaller or uniquely shaped ear canals, this same expansion can create pressure points, leading to discomfort over time. This subjectivity is not a flaw in the headphones, but a fundamental challenge of ergonomics. It underscores the fact that the “perfect fit” is a myth; the goal is always to design for the widest possible range of users, accepting that outliers will exist.

The Elegance of the Essential

In an age of relentless technological escalation, the Koss The Plug stands as a quiet testament to a different kind of ingenuity. It is a reminder that the most elegant solutions are often the simplest, and that a deep understanding of first principles can be more powerful than a thousand lines of code. It doesn’t cancel noise with digital signal processors; it absorbs it through the clever application of material science. It doesn’t require a battery, an app, or a firmware update. Its genius is entirely analog.

By combining the space-age legacy of memory foam with the timeless principles of the dynamic driver, Koss created more than just an earbud. They created an accessible tool for personal silence, a device that empowers users to curate their own acoustic environment. It proves that great design is not always about adding more, but about perfecting the essential. And in our noisy world, the simple, profound ability to choose what we hear is perhaps the most essential feature of all. By embracing this, and remembering to listen at volumes that respect the delicate miracle of our own hearing, we can fully appreciate the sound of silence, and the music that fills it.