ARC DFR Wired Earbuds in-Ear Headphones – Outstanding Sound Quality

Update on July 2, 2025, 2:59 p.m.

I spend my days in a world of oscilloscopes, frequency analyzers, and thousand-dollar headphones, chasing sonic perfection. So, you can imagine my curiosity when I stumbled upon a digital mystery: a pair of wired earbuds, the ARC DFR, selling for a laughably low $6.99. The price wasn’t the mystery, though. The real puzzle was in the user reviews. They read like reports on two completely different products.

On one side, you had Ginny, exclaiming, “WOW, they are FABULOUS! The bass and everything is great.” Then, in stark opposition, there was Hannah, who stated, “Not the greatest sound quality… at full volume it hurts my ears.” And the plot thickened. A user named Celtics fan, who has trouble with other earbuds falling out, celebrated that “these don’t.” Yet, for Rhea wilson, a simple drop from the bed to the carpet was a death sentence for her pair.

What was going on here? Were some people getting a secret premium version? As an audio engineer, I knew there was a more scientific explanation. This wasn’t a case for customer service; it was a case for acoustics. So, let’s put on our detective hats and deconstruct this $7 enigma.

The First Clue: Your Ear is a Concert Hall, and It’s Leaking

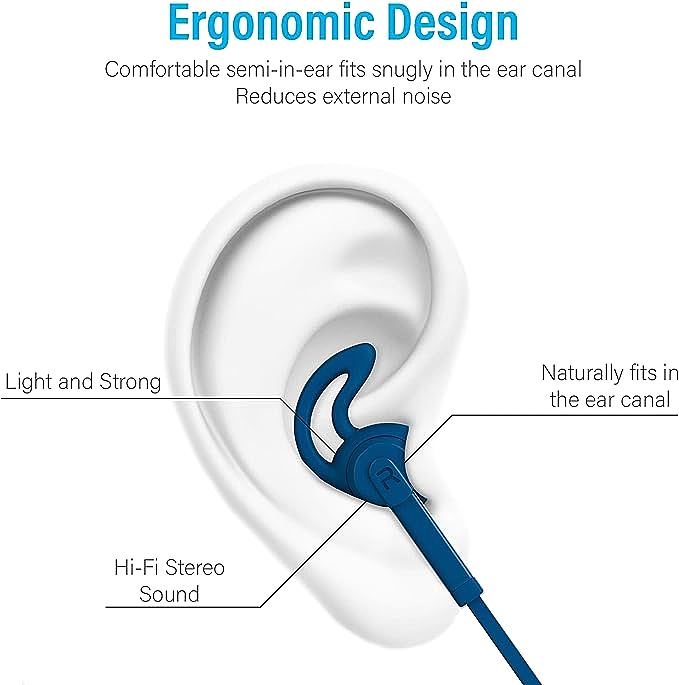

Before we even talk about speakers or wires, we have to talk about the most crucial, and most overlooked, component in your entire audio setup: the seal between the earbud and your ear. Think of your ear canal as a miniature concert hall. For you to experience rich, full-bodied sound, especially deep bass, that hall needs to have solid, insulated walls.

This is the science of passive noise isolation. The silicone tips of the ARC DFR are designed to act as a physical plug, blocking outside noise from crashing your private concert. But more importantly, they prevent the sound inside from escaping. Bass frequencies have long, powerful waves. If your concert hall has a leaky door—a poor seal—those waves simply spill out into the open air before they have a chance to be fully perceived by your eardrum.

This is the single biggest reason for the divided reviews. When Celtics fan says the earbuds “stay put,” they’re not just talking about comfort. They’re unknowingly praising a successful acoustic seal. They’ve locked the doors to their concert hall, so the bass stays in. Conversely, if the included ear tips don’t happen to fit your unique ear shape, you’re getting a leaky, thin sound, and no amount of driver quality can fix it. You’ve lost the battle before it’s even begun. It’s not just about a good fit; it’s about good physics.

Inside the Hall: A Tiny Orchestra with a Temperament

Assuming you’ve achieved that all-important seal, let’s venture inside our concert hall and meet the orchestra: the tiny speaker inside the earbud, known as a driver or transducer. Its job is to convert electrical signals from your phone into the physical vibrations that create sound waves.

This is where Ginny’s “FABULOUS” bass comes from. The engineers behind a budget product like this make smart compromises. They likely tuned the driver to excel in the low-frequency range, a crowd-pleasing move that gives music a satisfying punch. For $7, they built you a concert hall with a surprisingly good subwoofer.

But what about Hannah’s experience of ear-hurting sound at full volume? This points to a concept called Total Harmonic Distortion (THD). Imagine asking our tiny orchestra to play as loud as possible. A high-end, well-rehearsed orchestra can do it with clarity. A budget orchestra, however, might start to struggle. The instruments (the driver’s diaphragm) can’t vibrate perfectly in line with the music, creating extra, unwanted frequencies, or harmonics. This is distortion, and it often sounds harsh, brittle, or “hurts your ears.” The ARC DFR’s orchestra plays beautifully at a reasonable volume, but push it too hard, and its budget origins begin to show.

This is further complicated by psychoacoustics, the science of how our brains interpret sound. Our hearing sensitivity varies wildly from person to person. Hannah might simply be more sensitive to the specific high frequencies where this distortion occurs. It’s a reminder that sound is ultimately a personal experience, a collaboration between the headphone and your own unique brain.

The Supporting Cast: Wires, Plugs, and an Inevitable Gamble

The story doesn’t end with the driver. The supporting features have their own tales to tell. That flat, “tangle-free” cord isn’t just a gimmick; it’s simple material science. A round cable can twist and turn on itself in infinite ways, leading to knots. A flat cable, often made from a flexible material like TPE, has a much more limited range of motion, drastically reducing its ability to become a tangled mess in your pocket.

And then there’s the plug itself—the humble 3.5mm jack. Did you know this piece of “old” technology is a marvel of engineering that dates back to 19th-century telephone switchboards? The modern version, likely a TRRS (Tip-Ring-Ring-Sleeve) plug, cleverly packs four separate electrical contacts into one tiny connector, delivering left audio, right audio, a ground channel, and a microphone signal, all at once. It’s a testament to timeless, efficient design.

This brings us to the final clue: the durability gamble. When Rhea’s earbuds broke from a short fall, it wasn’t necessarily a defect. It was a predictable outcome of extreme cost-cutting. To hit a $7 price point, manufacturers use less robust plastics and simpler assembly methods. The product is engineered to work, but not necessarily to last through hardship. Buying a sub-$10 electronic device is an implicit gamble on its longevity.

The Verdict: A $7 Masterclass in Audio Engineering

So, what’s the solution to our mystery? The ARC DFR isn’t one product; it’s a spectrum of experiences, dictated by physics and probability. Its performance hinges almost entirely on achieving a perfect acoustic seal. If you win the “fit lottery,” you unlock a sound that dramatically outperforms its price tag. You get to enjoy the surprisingly capable bass from its tiny orchestra.

If you lose that lottery, or if you’re a critical listener who pushes the volume, you’ll be confronted with its limitations. The earbuds themselves are a masterclass in compromise. The engineers poured their entire minuscule budget into the single most important factor—creating the potential for good sound via a sealed in-ear design—while sacrificing longevity and high-volume performance.

Ultimately, these earbuds aren’t just a product; they are a lesson. They teach us that a good fit is paramount, that all sound is subjective, and that appreciating the engineering choices behind everyday objects is a reward in itself. For anyone curious about the science of sound, the ARC DFR is arguably the best $7 you could ever spend on your education. Just remember to listen at a safe volume—as the World Health Organization advises, keeping it below 85 decibels is key to preserving your hearing for a lifetime of listening. After all, the best concert hall is the one you can enjoy for years to come.