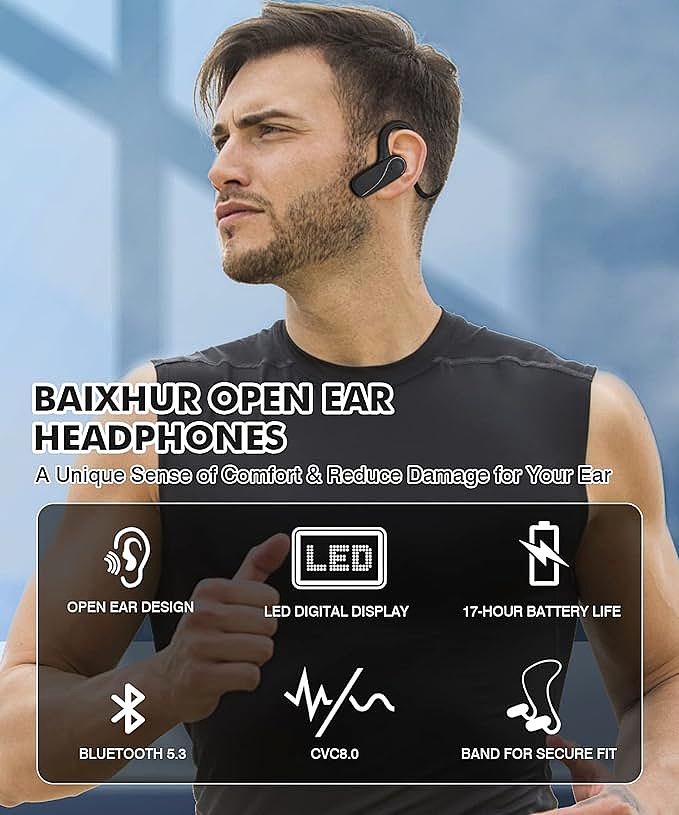

Baixhur BH-OEH-05 Open Ear Headphones: A Budget-Friendly Wireless Option for Active Lifestyles

Update on July 2, 2025, 10:37 a.m.

It’s a familiar scene on any city street, in any park, on any given day. A jogger, lost in the rhythm of their playlist, a focused expression on their face. A cyclist silently approaches from behind, a gentle bell chime lost to the thumping bass in the runner’s ears. A near-miss, a startled jump, and a shared moment of adrenaline. This isn’t a story about carelessness; it’s a story about technology working exactly as designed. For the better part of a century, the holy grail of personal audio has been isolation—the creation of a perfect, sound-proof bubble to shield us from the world and immerse us in a universe of our own choosing.

From the hefty, head-clamping cans of early aviation to the sleek, noise-canceling pods that are now ubiquitous, the engineering goal has been singular: seal the ear, kill the noise, and deepen the immersion. We’ve gotten remarkably good at it. But in our successful quest to shut the world out, we’ve started to realize what we’ve lost: a connection to the very environment we move through. What if the next great leap in audio technology isn’t about building a better bubble, but about elegantly popping it?

This question is at the heart of a quiet revolution in audio design, a movement championing a different philosophy: integration over isolation. It’s a philosophy embodied by a growing category of devices known as open-ear headphones, and by examining a specific example like the Baixhur BH-OEH-05, we can deconstruct the fascinating science that allows us to have our world and hear it, too.

The Magic of Guided Air

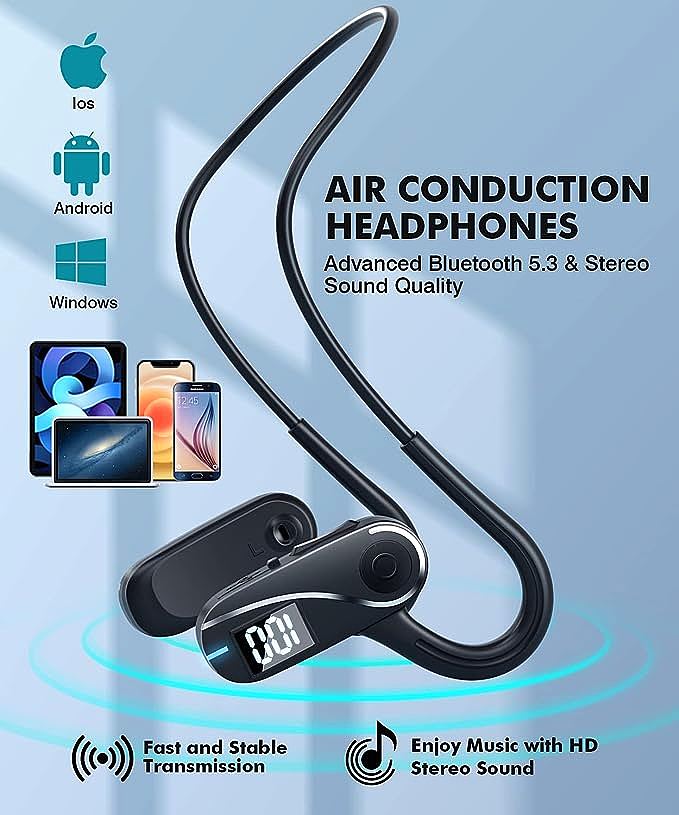

At first glance, an open-ear headphone looks slightly strange. It doesn’t plug your ear or cover it. Instead, it rests just in front, seemingly broadcasting sound into the general vicinity. The magic, however, lies in a principle called air conduction, which is both surprisingly simple and clever. Think of it this way: instead of shouting into a sealed tube (like an in-ear headphone), it’s like a person leaning in to deliver a precise, directed whisper that only your ear is positioned to catch. The sound travels through the air, its natural medium, to your eardrum, leaving your ear canal completely open to receive all the other ambient sounds of your environment—the approaching car, a colleague’s question, the chirping of birds.

This approach immediately solves the isolation paradox. But, as with all things in physics, it comes with a fascinating trade-off, particularly concerning one of music’s most visceral elements: bass. The “thump” you feel from a deep bass note in traditional headphones is a product of sound pressure building up in the small, sealed volume of your ear canal. It’s like hitting a drum in a small, tiled bathroom; the sound waves bounce around, reinforcing each other and creating a powerful physical sensation. An open-ear design is like hitting that same drum in the middle of an open field. The sound wave is just as real, but it dissipates into the vast space according to the inverse-square law, its energy diminishing rapidly with distance. It doesn’t build up pressure against your eardrum. The result is a sound profile that is often described as clear and crisp, but with a lighter, more ethereal bass. For some, this is a deal-breaker. For others, it’s a small price to pay for reclaiming their auditory connection to the world.

The Invisible Handshake of a Stable Connection

Of course, modern listening is a wireless affair, and the quality of that experience hinges entirely on the invisible dance of radio waves. The Baixhur headphones leverage Bluetooth 5.3, and understanding why that number matters goes beyond simple marketing. Imagine the 2.4 GHz frequency band—used by Wi-Fi, microwaves, and countless other devices—as a spectacularly crowded cocktail party. Everyone is talking at once. Early Bluetooth was like a guest who would try to shout over the noise, often getting interrupted and having to repeat themselves (this is what we experience as stuttering or dropouts).

Bluetooth 5.3, however, is a much more sophisticated guest. Its key feature is an enhanced ability to rapidly scan the “room,” identify which “conversations” (channels) are already too crowded, and intelligently hop to a quieter spot to maintain a clear, stable dialogue with your phone. This process, known as channel classification, happens thousands of times a second. It means less energy is wasted on re-transmitting failed data packets, which is a crucial part of the efficiency equation. This isn’t just a theoretical benefit; it’s a direct contributor to how a small, lightweight device can achieve a claimed 17 hours of music time on a single charge. It’s a testament to smarter software making better use of finite battery power.

The Art of the Clean Voice in a Noisy World

A headphone’s utility often extends to phone calls, and this is where another piece of sophisticated software comes into play: CVC 8.0 (Clear Voice Capture). It’s vital to understand that CVC is not for you; it’s for the person you’re talking to. It doesn’t make your world quieter. Instead, it acts as an intelligent bouncer for your microphone.

When you speak, the microphone picks up everything: your voice, the wind, the café chatter, the traffic. The CVC algorithm, a feat of digital signal processing, is trained to recognize the specific frequency patterns of human speech. It effectively listens to the entire audio input and says, “That part—the part that sounds like a person talking—that’s the VIP. Let it through. Everything else? That’s background noise. Turn its volume down.” As one user of the Baixhur headset noted, it allows people on the other end to hear you clearly, a common pain point for many wireless devices. It’s a clever bit of audio filtering that makes seamless communication possible, even when your environment is anything but quiet.

The Human Factor: Comfort, Reality, and Unanswered Questions

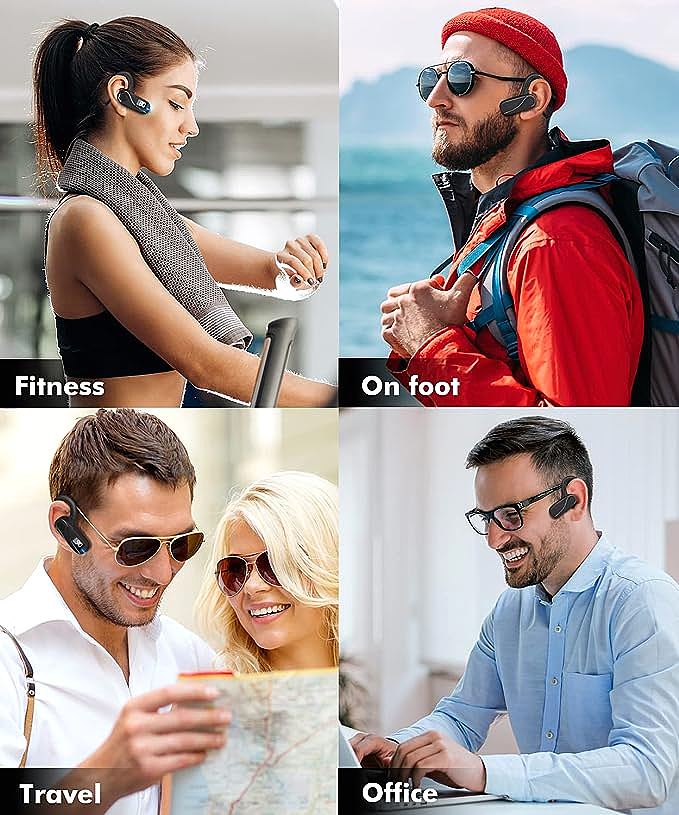

Beyond the pure technology, the open-ear design carries significant ergonomic benefits. With nothing inserted into the ear canal, there’s no pressure or irritation, making them comfortable for all-day wear. However, when a product is marketed for sports, reality introduces new variables, chief among them, sweat. One user review for the Baixhur headphones noted potential issues during running, which highlights a critical piece of missing information in the provided data: an IP (Ingress Protection) rating. This standardized scale (e.g., IPX4, IPX5) is the universal measure of a device’s resistance to water and dust. Without a stated IP rating, a consumer can’t be certain of the headphones’ durability under strenuous, sweaty conditions. This isn’t a flaw in the technology itself, but a crucial detail for making an informed decision, and its absence underscores the importance of looking beyond features to standardized specifications.

Ultimately, open-ear headphones like the Baixhur BH-OEH-05 are not designed to be your primary audio device for a transatlantic flight or a deep listening session of a classical symphony. They will not replace the immersive, high-fidelity experience of premium noise-canceling headphones. Instead, they represent the creation of a new and vital category of audio tool. They are designed for the moments in between, for the fluid reality of modern life where we are constantly transitioning between digital focus and physical interaction. They are for the parent who wants to listen to a podcast while keeping an ear out for their playing child, the cyclist who needs navigation prompts without losing track of traffic, and the office worker who enjoys background music but doesn’t want to miss being a part of the team.

They are a step away from the sound-proof bubble and a step toward a future where technology doesn’t demand our full attention but rather augments our reality. The quiet revolution isn’t about shouting louder; it’s about learning to listen, to everything, all at once.