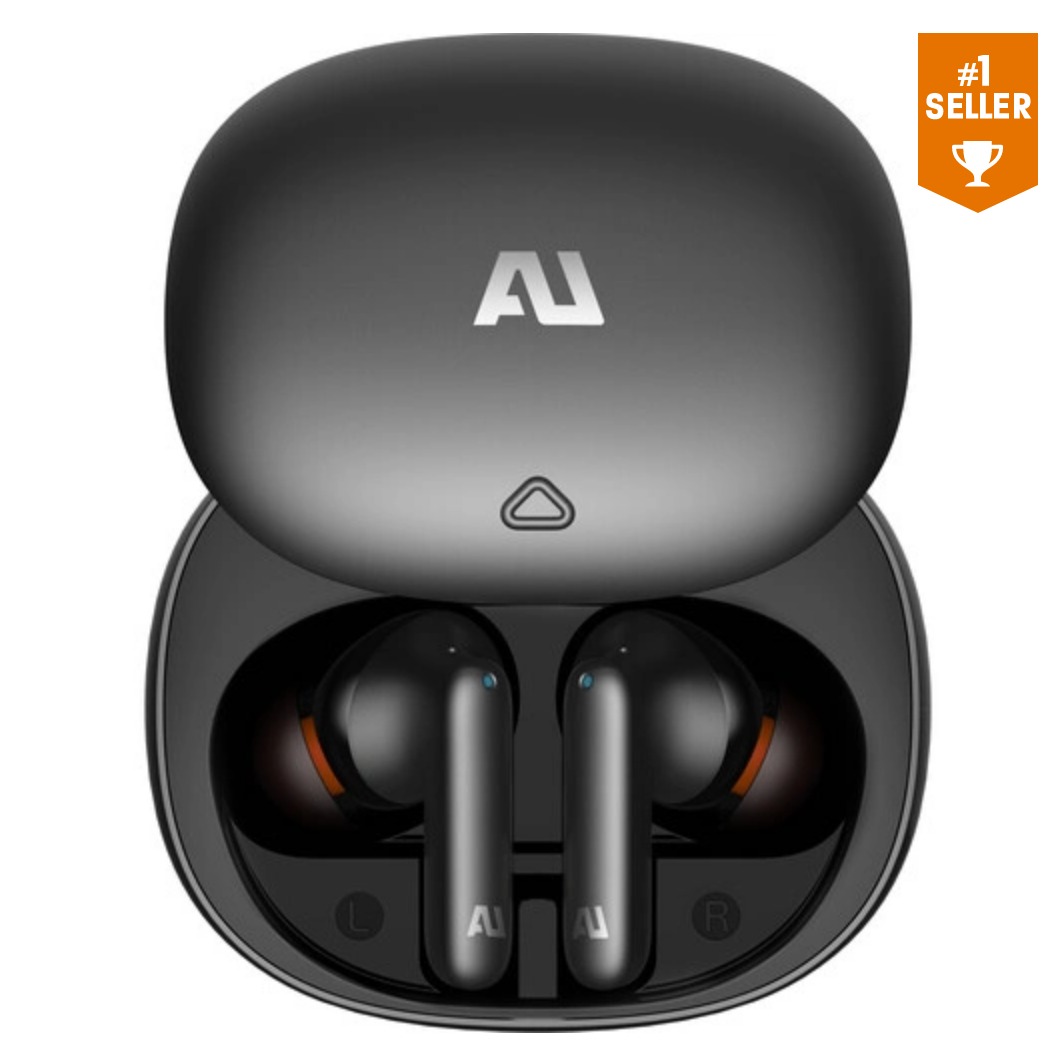

NVAHVA A68 True Wireless Earbuds: Tiny yet Mighty Bluetooth Earbuds

Update on July 1, 2025, 8:54 a.m.

There’s a dream many of us share in our hyper-connected world: the dream of a personal soundtrack that simply is. No clumsy wires catching on door handles, no bulky cans messing up our hair, no awkward white stems dangling from our ears. Just pure, private sound, flowing directly into our consciousness. For years, this dream felt like a luxury, a privilege reserved for those willing to invest heavily in high-end tech. And then, something like the NVAHVA A68 True Wireless earbud appears, offering a piece of that dream for the price of a few cups of coffee.

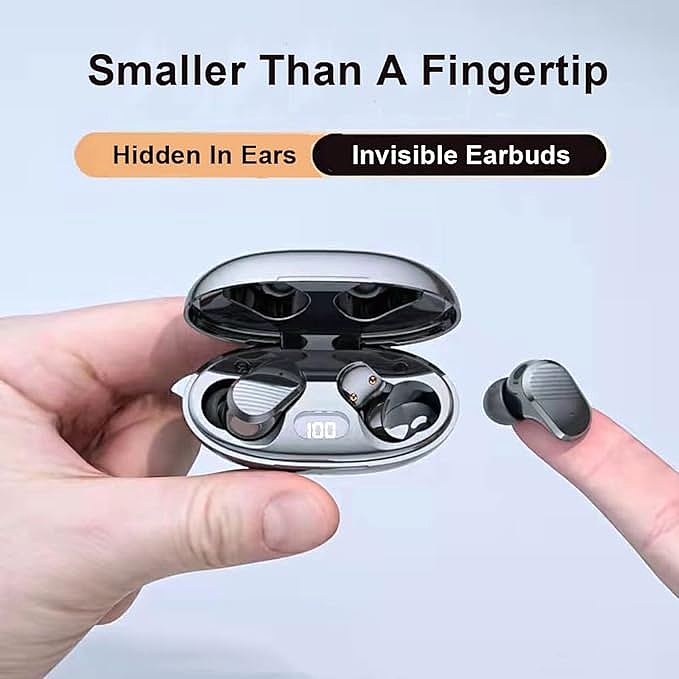

On the surface, it’s an impossibly tiny, feather-light piece of black plastic. It promises invisibility, comfort for sleepers, and a full day of music. But this apparent simplicity is an illusion. Hiding within its minuscule 13.7-millimeter shell is a universe of sophisticated engineering, a story of scientific achievement, and, most fascinatingly, a masterclass in the art of the compromise. To truly understand this $15 marvel, we have to peel back the layers, starting with the very shell that promises to make it disappear.

The Art of Weighing Nothing

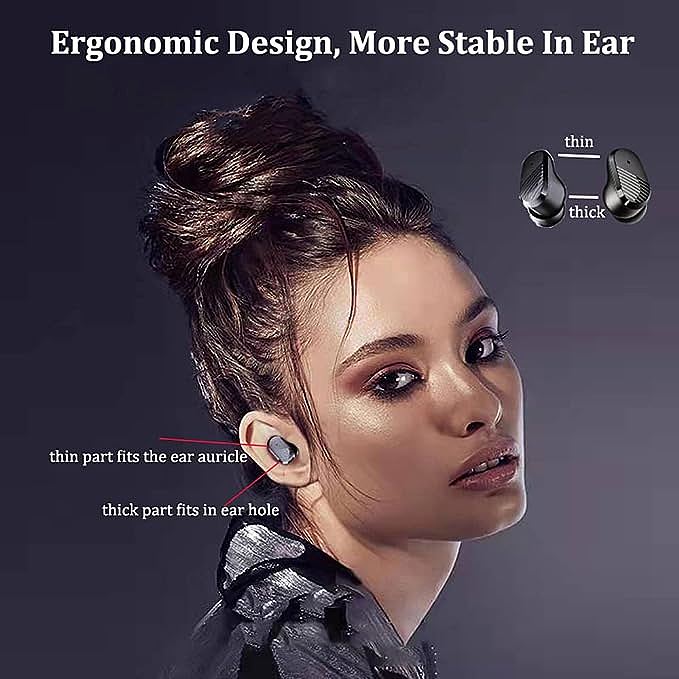

Pick up one of the A68 earbuds. At 3.5 grams, it feels like almost nothing. This profound lightness isn’t an accident; it’s a deliberate engineering choice rooted in material science. The body is forged from Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene, or ABS—a polymer you’ve encountered thousands of times in everything from LEGO bricks to car bumpers.

Think of the earbud’s shell as the fuselage of a highly advanced model aircraft. For a device intended to live in your ear for hours, potentially even through the night, every microgram counts. ABS is the perfect material for this mission. It possesses a remarkable strength-to-weight ratio, meaning it can be both durable and incredibly light. More importantly, as a thermoplastic, it can be injection-molded with microscopic precision. This isn’t just for looks; the exact shape and rigidity of the earbud’s internal chamber are critical to its acoustic performance. The smooth, seamless exterior is the first clue that this isn’t just a cheap piece of plastic—it’s the result of carefully calculated manufacturing, the first layer of the magic trick.

A Concert Hall in a 10mm Space

Now, for the soul of the device: the sound. The specifications boast a 10mm triple-layer composite driver. In the world of tiny earbuds, a 10mm driver is like putting a surprisingly large engine in a very small car. The fundamental law of acoustics dictates that to produce deep, satisfying bass, you need to move a significant amount of air. How can such a tiny object accomplish this?

Let’s imagine the driver as a miniature orchestra. The permanent magnet is the concert hall itself, providing the foundational magnetic field. The voice coil is the conductor, rapidly moving back and forth as it receives electrical signals from your phone. But the true star is the diaphragm—the thin membrane that vibrates to create sound waves. In this case, it’s the entire string section.

A standard, single-layer diaphragm is like an orchestra with only violins; it might be great at high notes but lacks depth. The A68’s “triple-layer composite” diaphragm, however, is like a full string section. One specialized layer, likely a rigid material like PEEK, handles the crisp, clear notes of the violins (treble). Another, more flexible layer, perhaps polyurethane, provides the rich, warm tones of the violas (mid-range vocals). And a third layer is optimized to provide the deep, resonant thrum of the cellos and double basses (bass). By bonding these disparate materials into a single, cohesive unit, engineers can “tune” the driver to perform far beyond the physical limitations of its tiny enclosure. It’s a clever acoustic workaround, a way to fight physics to deliver a surprisingly full sound from an impossibly small space.

The Ghost in the Machine

For all its clever engineering, the A68 is a creature of its price point, and nowhere is this more apparent than in the user experience. The Amazon page is a fascinating study in contradiction. Users praise the comfort and sound quality for the price, but a consistent thread of frustration emerges: “they are so touchy!” One user laments accidentally pausing songs, making calls, or summoning Siri while simply trying to adjust the earbud in their ear.

This isn’t a simple “flaw.” It’s a profound human-computer interaction problem, born from the very design goal of invisibility. In the quest to eliminate all physical buttons for a smooth, seamless surface, designers rely on capacitive touch. Your fingertip completes a tiny electrical circuit on the earbud’s surface to register a command. The problem is, so does your pillow.

This is the hidden cost of aesthetic minimalism. Without the tactile, reassuring click of a physical button, our brains struggle. We lack the precise feedback to know if we’ve tapped once, twice, or are about to hold for 1.5 seconds. This is a concept in psychology known as cognitive load; when an interface is ambiguous, our brain has to work harder, leading to errors and frustration. A more expensive earbud might invest in more sophisticated sensors, accelerometers that can distinguish between an intentional tap and an accidental brush, or even pressure-sensitive surfaces. The A68, in its relentless pursuit of low cost, cannot. It’s a stark reminder that in product design, every choice is a trade-off. The elegance of its form creates a phantom limb in its function—a ghost in the machine that you command with a whisper but can awaken with a stray touch.

An Echo of Value

So, what is the NVAHVA A68 in the grand scheme of things? It is not a high-fidelity instrument for the discerning audiophile. It is not a flawlessly executed piece of premium hardware. It is something far more interesting. It’s an artifact of 21st-century manufacturing, a testament to how decades of cumulative progress in materials, acoustics, battery chemistry, and supply chain logistics can culminate in a device that is functionally miraculous for its cost.

It delivers a huge portion of the true wireless freedom that once cost hundreds of dollars, and it does so by making a series of intelligent, deliberate, and sometimes frustrating compromises. It’s a tiny vessel, engineered to the very edge of its limitations, offering a journey into the convenience of modern audio. It doesn’t promise a perfect journey, but for fifteen dollars, it offers a ticket to the show. And in that, there’s a kind of honest, unpretentious value that is hard not to admire. It doesn’t give you a simple answer about what “good” is, but it asks a much better question: What is value, really?