The Science of Silence: Why Passive Isolation Remains the Gold Standard in a Noise-Polluted World

Update on Jan. 10, 2026, 4:07 p.m.

In an era defined by relentless sensory bombardment, silence has become the ultimate luxury. We live in a soundscape cluttered with the roar of jet engines, the hum of open-plan offices, and the ceaseless digital chirping of notifications. The modern response to this acoustic assault has largely been technological: the widespread adoption of Active Noise Cancellation (ANC). Marketing campaigns promise us a “cone of silence” generated by sophisticated algorithms and inverted sound waves. However, beneath the hype of computational audio lies a simpler, more profound, and immutable truth of physics.

True silence is not created by adding more noise; it is achieved by physically excluding it. This is the domain of Passive Sound Isolation, a principle as old as architecture itself but refined to a microscopic art form in professional audio monitoring. While the consumer market chases the latest battery-powered noise-cancelling wizardry, audio professionals, musicians, and discerning audiophiles continue to rely on the steadfast reliability of physical isolation. This divergence isn’t about nostalgia; it’s about the fundamental laws of acoustics, the biology of human hearing, and the pursuit of unadulterated sound.

Understanding the distinction between “cancelling” noise and “isolating” from it is crucial for anyone seeking not just better audio quality, but better auditory health. This exploration will take us through the physics of sound waves, the history of stage monitoring, and the anatomical realities of the human ear, using the Shure AONIC 215 Wired Sound Isolating Earbuds as a primary case study. This device serves not merely as a product, but as an archetype of a design philosophy that prioritizes physical acoustic sealing over digital manipulation.

The Physics of the Barrier: Understanding Sound Isolation

To appreciate the elegance of passive isolation, one must first understand the enemy: sound itself. Sound travels as a mechanical wave, a vibration propagating through a medium like air. When these waves encounter a barrier, three things happen: some energy is reflected, some is absorbed, and some is transmitted. The goal of any isolation device is to minimize transmission.

The Mass Law and the Seal

The fundamental principle governing this is known as the Mass Law. In architectural acoustics, it states that the heavier and denser a barrier is, the harder it is for sound waves to vibrate it and pass through. However, you cannot strap a concrete wall to your head. Therefore, in-ear monitors (IEMs) rely on a different, equally powerful principle: the Acoustic Seal.

Imagine a room with a heavy, soundproof door. If that door is left ajar even by a fraction of an inch, the soundproofing capability of the entire room collapses. Sound behaves like water; it will find the path of least resistance and leak through any gap. This is where the engineering of the Shure AONIC 215 distinguishes itself. By utilizing a nozzle design that inserts directly into the ear canal, coupled with compressible memory foam sleeves, it creates an airtight seal. This seal effectively extends the density of the earphone’s shell into the ear canal itself, blocking the air pathway that sound waves require to travel.

The Frequency Spectrum Battle

This is where the battle between Active Noise Cancellation (ANC) and Passive Isolation is most fiercely fought. ANC works by using microphones to “listen” to incoming noise and generating an “anti-noise” wave with the opposite phase. When the two waves collide, they cancel each other out. This works exceptionally well for low-frequency, constant drones—like the hum of an airplane engine.

However, physics dictates that high-frequency sounds have very short wavelengths. These waves change direction and phase so rapidly that current ANC chips often struggle to keep up. The result is a “hiss” or a failure to block sudden, sharp sounds like a crying baby or a clattering dish. Passive isolation, governed by the physical barrier, does not discriminate. It attenuates sound across the entire frequency spectrum. A 37 dB reduction achieved through physical sealing applies to the rumble of a subway train and the screech of its brakes alike. It provides a consistent, natural reduction of the world’s volume, rather than a digitally processed, frequency-dependent silence.

The History of Hearing Protection: From Industry to Stage

The concept of inserting a barrier into the ear canal didn’t start with music; it started with survival. In the industrial boom of the 20th century, factory noise levels soared, leading to a generation of workers with profound hearing loss. The first earplugs were crude tools of industrial hygiene. However, the leap from “blocking sound” to “delivering sound while blocking noise” occurred in a different high-volume environment: the rock concert stage.

The Monitor Crisis

By the 1970s and 80s, stage volumes had escalated to dangerous levels. Musicians stood in front of massive “wedge” monitor speakers blasting their own mix back at them so they could hear themselves over the drums and amplifiers. This created a vicious cycle: the band played louder, so the monitors had to be turned up louder, leading to feedback loops and, tragically, permanent hearing damage for countless icons of rock.

The solution was the In-Ear Monitor (IEM). By placing a tiny speaker directly in the ear canal and sealing it off with a custom mold or foam tip, audio engineers could kill two birds with one stone. First, they blocked out the deafening stage noise (passive isolation). Second, because the background noise floor was dropped by 20-30 decibels, the music could be fed directly to the musician’s eardrum at a much lower, safer volume.

This technology, once the exclusive domain of stadium tours, has trickled down to the consumer level. The Shure AONIC 215 is a direct descendant of these professional tools. Its “Sound Isolating” nomenclature is not a marketing term; it is a technical description of its function as a protective barrier. When you wear them on a subway, you are essentially utilizing the same technology a drummer uses to protect their hearing from a crashing cymbal three feet away.

Anatomy of the Perfect Fit

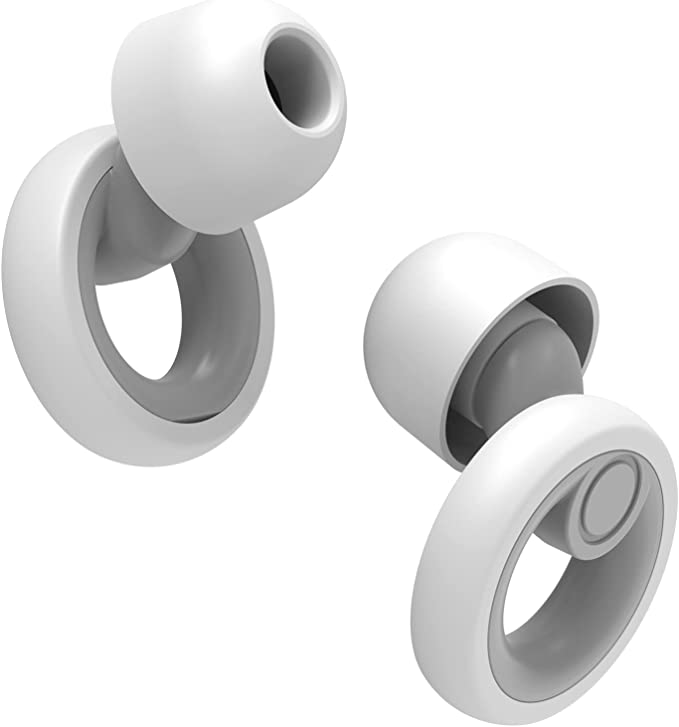

The effectiveness of any passive isolation device relies entirely on the interface between the machine and the biology. The human ear canal is not a straight, smooth tube; it is a curved, S-shaped tunnel lined with sensitive skin and capable of changing shape slightly as the jaw moves. Designing a rigid object to seal this organic tunnel is a complex ergonomic challenge.

The Role of Material Science

This is why the choice of eartip material is as critical as the driver itself. Silicone tips rely on the elasticity of the flange to push against the ear canal walls. They are durable and easy to clean, but they don’t always create a perfect seal for every ear shape.

The “black foam sleeves” often praised in reviews of the AONIC 215 represent a different approach. These are made from heat-activated viscoelastic polyurethane foam. When compressed, they become narrow enough to insert deep into the canal. As they absorb body heat, they expand, conforming to the microscopic irregularities of the ear canal’s specific geometry. This creates a custom-fitted plug every time they are inserted.

This mechanism is responsible for the documented “37 dB” isolation figure. To put that number in perspective, 37 dB is roughly the difference between a busy street corner and a quiet library. Achieving this reduction without batteries requires a fit that is both deep and secure. This is also why the AONIC 215 features the distinctive “over-the-ear” wire design. By routing the cable over the top of the ear, the weight of the cable is supported by the ear structure, preventing the seal from breaking when the user moves their head or runs.

Audio Hygiene: The Health Case for Isolation

In public health discourse, we often talk about “light pollution” or “air pollution,” but “noise pollution” is an equally pervasive threat. Chronic exposure to high noise levels triggers the release of cortisol, the stress hormone, leading to hypertension, sleep disturbance, and cardiovascular issues.

The Volume Wars

For headphone users, the danger is often self-inflicted. When in a noisy environment—like an airplane cabin measuring 80 dB—a user with open-back headphones or poor isolation must turn their music up to 90 or 95 dB just to hear it clearly over the background noise. This “masking” effect forces the user to blast their ears with dangerous sound pressure levels just to achieve a perceptible signal-to-noise ratio.

Passive isolation flips this equation. By lowering the ambient noise floor by ~37 dB, the Shure AONIC 215 allows the user to listen to music at 60 or 70 dB while perceiving it as loud and clear. This difference is monumental. According to NIOSH (National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health) standards, exposure to 95 dB is safe for less than an hour, while 70 dB is safe indefinitely.

Therefore, high-quality passive isolation is not just about better bass response or clearer vocals; it is a preventative health measure. It allows for “critical listening”—hearing the texture of a cello or the decay of a reverb tail—without the auditory fatigue that comes from battling background noise.

The Case Study: Shure AONIC 215 as a Reference

We analyze the Shure AONIC 215 not to review it as a consumer gadget, but to understand it as a reference implementation of these acoustic principles. Its design choices reflect a prioritization of physics over electronics.

The Single Driver Philosophy

In a market obsessed with “more”—more drivers, more microphones, more chips—the AONIC 215 utilizes a single dynamic driver. This seemingly simple choice eliminates the need for complex crossover networks (which split frequencies between multiple drivers), ensuring phase coherence. Because all sound originates from a single point, there are no timing alignment issues that can muddy the soundstage. This clarity is essential for professionals who need to make split-second decisions based on what they hear, but it offers the casual listener a highly organized and rhythmic presentation of music.

The Maintenance of longevity

Passive isolation devices have another advantage: longevity. ANC headphones rely on built-in lithium-ion batteries that inevitably degrade over 2-3 years, turning expensive headphones into e-waste. A passive device like the AONIC 215 has no battery to die and no firmware to become obsolete. As noted by long-term users, common issues like a drop in volume are often due to simple physical blockages (earwax) in the nozzle, which can be cleared with a tool, restoring the device to factory performance. This maintainability, combined with the detachable MMCX cable system, positions it as a tool meant to last a decade, not a disposable accessory.

Future Trends: The Return to Analog Silence

As we look toward the next 3-5 years of audio technology, we see a fascinating bifurcation. On one path, computational audio will continue to advance, with AI-driven noise cancellation becoming more predictive. However, a parallel trend is emerging: a “digital detox” of the signal chain.

Users are becoming increasingly aware of the fatigue caused by “anti-noise” pressure on the eardrums and the artificiality of digitally processed silence. There is a growing appreciation for the “black background” that only physical isolation can provide. Just as vinyl records returned for their tangible, analog nature, passive isolation is being recognized as the “organic” alternative to synthetic silence.

Furthermore, as remote work and nomadic lifestyles normalize, the reliability of wired, passive isolation becomes a premium asset. A device that never needs charging, never suffers from Bluetooth interference, and provides studio-grade isolation anywhere on the planet is the ultimate tool for the focused professional.

The Shure AONIC 215 stands as a testament to the enduring power of basic physics. In a world trying to solve noise with more noise, it reminds us that sometimes, the most sophisticated solution is simply to build a better wall. By understanding and utilizing the principles of mass, seal, and fit, we can reclaim our auditory space, protecting our hearing and preserving the sanctity of the music we love.