Apple AirPods Max Wireless Over-Ear Headphones: A Luxurious Listening Experience

Update on June 30, 2025, 9:25 a.m.

There is a sound to the modern world, a relentless hum composed of traffic, construction, overlapping conversations, and the digital chimes of a thousand notifications. It is a constant, low-grade fever of the senses. In this chaos, we yearn for a sanctuary. Not necessarily an escape, but a space of clarity, a pocket of quiet where our own thoughts can finally be heard. For decades, achieving this personal silence was a physical act: closing a door, finding a remote park, waiting for the dead of night. Today, we are learning to build it, to architect it with silicon and software.

This is a story about the architecture of silence, and how the quest to control what we hear is fundamentally reshaping our perception of reality itself.

A Spark in the Sky

Our story begins not in a sterile lab, but 30,000 feet in the air. In 1978, Dr. Amar Bose, a professor at MIT and founder of the eponymous audio company, was on a transatlantic flight. He put on the airline-provided headphones, hoping to enjoy some music, only to find the delicate notes utterly consumed by the roar of the jet engines. In that moment of frustration, an idea sparked: what if you could use a microphone to capture the engine’s noise, and an electronic circuit to create an “anti-noise” signal to cancel it out before it reached the ear?

It was a revolutionary concept, rooted in a fundamental principle of physics known as destructive interference. Every sound is a wave with peaks and troughs. If you can generate a second wave that is a perfect mirror image—a trough for every peak, a peak for every trough—the two waves will annihilate each other, resulting in silence. Dr. Bose’s vision was to wage a war of physics, using sound to fight sound.

The initial challenge, however, was immense. The “brain” required to analyze the noise and generate a precise anti-noise signal in real-time, without any perceptible delay, was beyond the reach of the analog technology of the era. The quest for perfect, portable quiet would have to wait for the digital revolution to provide a mind fast enough for the task.

An Orchestra of Cancellation

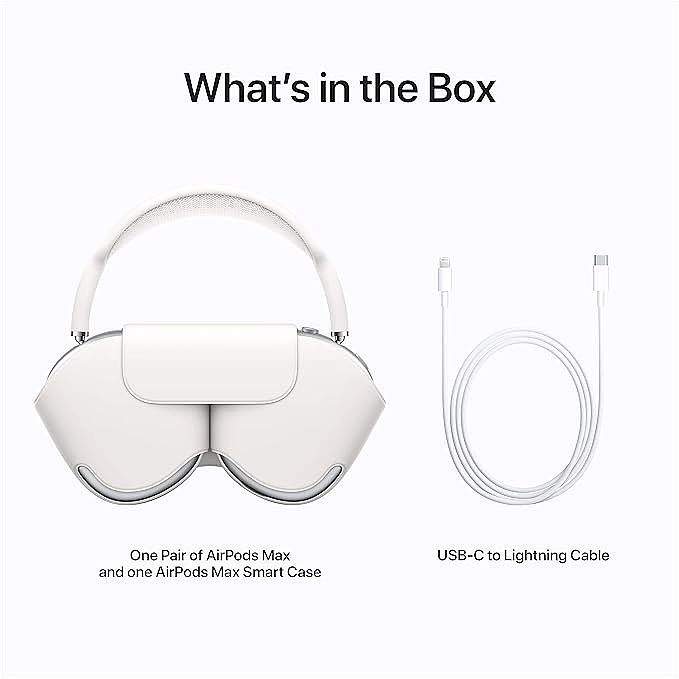

Fast forward to the present. A device like the Apple AirPods Max is the culmination of that decades-long quest. The principle remains the same, but the execution has evolved into a breathtakingly complex digital performance. To understand it, it’s best to think of it not as a single action, but as a symphony orchestra performing a concert of cancellation.

The “ears” of this orchestra are the eight external microphones embedded in the aluminum earcups. They are constantly listening to the outside world, capturing the ambient chaos and feeding it to the conductor. The conductor is the Apple H1 chip, a tiny silicon brain that resides in each earcup. Its task is monumental. It performs a type of rapid mathematical process known as a Fourier Transform, deconstructing the complex noise into its fundamental frequencies. Then, in a sliver of a millisecond, it computes and generates the precise, inverted “anti-noise” wave.

But the performance isn’t complete. There is a ninth microphone inside each earcup, acting as the orchestra’s discerning concertmaster. It listens to what your ear is actually hearing, checking for any stray noise that might have leaked past the plush memory foam cushions or any imperfections in the anti-noise signal. This crucial feedback loop allows the H1 chip to continuously self-correct, fine-tuning its output hundreds of times per second. Silence, it turns out, is not an absence, but a meticulously constructed and constantly maintained presence.

The Cathedral of Sound

Canceling the world is only half the story. The true revolution lies in what happens next: the creation of a new world of sound, built just for you. This is the domain of Computational Audio, a paradigm shift where software and processing power become as important as the physical drivers and magnets. These headphones are no longer just speakers; they are digital sculptors of sound.

This sculpting begins with understanding the listener. The way you perceive sound is as unique as your fingerprint. The precise shape of your head and the folds of your outer ear create a personal acoustic filter, influencing how sound waves reach your eardrums. Scientists call this your Head-Related Transfer Function (HRTF). Using an iPhone’s TrueDepth camera, the system can create a 3D map of your ear’s geometry, building a personalized profile. It learns the acoustics of you, tuning the audio to match how your brain is naturally wired to process sound.

With this “fingerprint of hearing,” the device can construct a virtual cathedral of sound around you. This is the magic of Personalized Spatial Audio. Using built-in gyroscopes and accelerometers, the headphones track the minute movements of your head relative to your screen. When you turn your head, the H1 chip instantly recalculates the soundscape, keeping the audio anchored to the device. The effect is uncanny. The sound no longer feels piped into your ears; it feels present in the room with you, creating a stable, unwavering acoustic stage.

At the heart of this is an unseen artist: the Adaptive EQ. The internal microphone constantly monitors the sound between the driver and your eardrum, analyzing how the seal of the earcups affects the frequency response. Did you put on glasses, slightly breaking the seal and letting some bass escape? The H1 chip detects this and instantly adjusts the low- and mid-frequencies to compensate, ensuring the audio remains rich and consistent. It’s a continuous, invisible act of calibration, all in the service of a perfect listening experience. This reliance on a closed loop of hardware and software is also why the system works best within its own ecosystem, using the efficient AAC codec over Bluetooth. It’s a deliberate engineering trade-off: sacrificing universal support for a more deeply integrated and controlled experience.

The Curated Self

What begins with a desire for quiet ends with something far more profound. These devices are evolving beyond passive playback tools into active editors of our perceived reality. They represent a powerful new ability to curate our sensory input—to subtract the chaotic, and to add the beautiful, the immersive, the personal.

The implications are vast. We are standing at the threshold of an era of augmented hearing, where a layer of intelligent, contextual sound can be seamlessly woven into our daily lives. The line between the sound of the world and the sound of our choosing will continue to blur. The architecture of silence was just the first step. The next is the architecture of reality itself. And it leaves us with a question to ponder: when we can so perfectly sculpt the world we hear, who do we become?