Spobri Open Ear Wireless Headphones: Experience Comfort and Awareness

Update on Sept. 13, 2025, 1:53 p.m.

You’re walking down a busy city street, the rhythmic beat of a podcast in your ears. A car horn blares to your left. A cyclist’s bell chimes urgently from behind. A snippet of conversation drifts from the café you’re passing. Your brain, an astonishingly sophisticated audio processor, is constantly working, filtering, and prioritizing this cacophony. It’s performing a feat so remarkable that scientists named it after the one place it seems most impossible: the “cocktail party effect.” This is your innate superpower—the ability to focus on a single voice or sound amidst a sea of noise, while still maintaining a crucial, low-level awareness of your surroundings.

For the last forty years, since the dawn of the Walkman, our personal audio technology has been largely designed to defeat this superpower. From foam-padded cans to noise-canceling earbuds that create an almost unnerving silence, the goal has been to build an ever-thicker, more perfect wall of sound. We created personal sound bubbles to escape the world, to focus, to immerse. But in doing so, we’ve started to realize what we’ve lost: connection, safety, and a fundamental sense of place. We’ve been systematically unlearning how to listen to the world.

Now, a different design philosophy is emerging, one that seeks not to isolate us from reality, but to integrate our digital soundscapes within it. This is the principle behind open-ear audio, a technology that represents less of an iteration and more of a quiet revolution in how we relate to sound.

A Tale of Two Pathways to Hearing

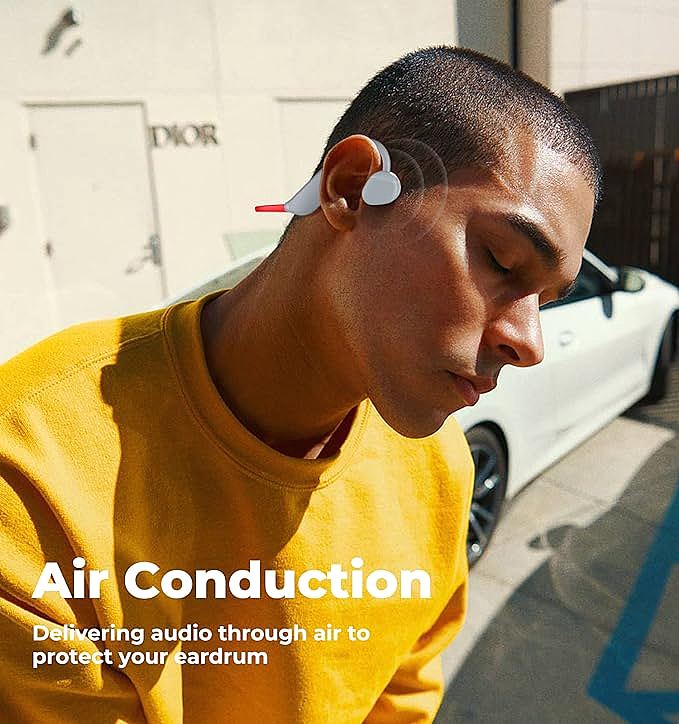

To understand this shift, you first have to appreciate the miracle of your own hearing. The primary way you perceive sound is through what is elegantly known as air conduction. Sound waves travel through the air, are funneled by your outer ear into the ear canal, and vibrate your eardrum. It’s a beautifully simple and effective system.

But there is another, more esoteric path: bone conduction. Sound can also be transmitted as vibrations directly through the bones of your skull to your inner ear, bypassing the eardrum entirely. Legend has it that the composer Ludwig van Beethoven, as his hearing failed, discovered he could still perceive the notes of his piano by biting down on a wooden rod pressed against the instrument. This same principle is used today in some military communication systems and specialized headphones.

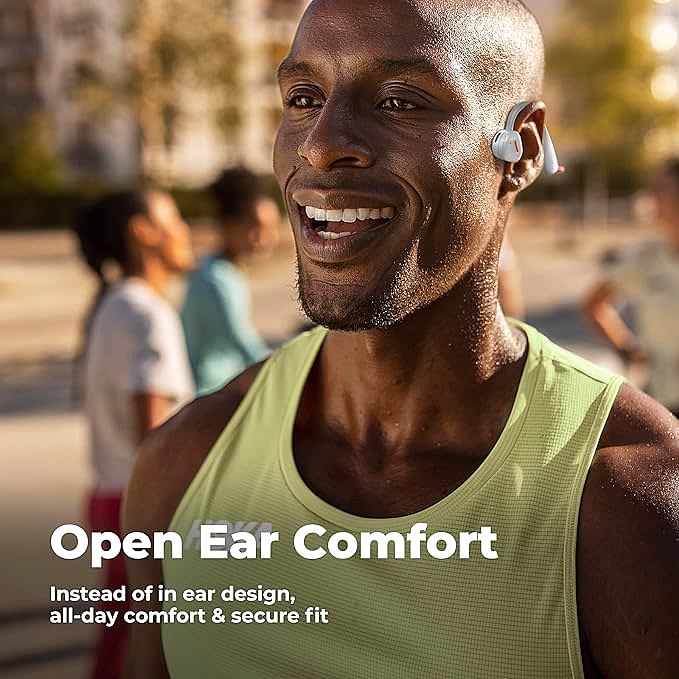

Open-ear audio technology primarily embraces the first path, air conduction, but in a radically new form. Instead of plugging the ear canal, devices like the Spobri air conduction headphones position a miniature, high-quality speaker just outside it. They generate precise sound waves that travel that final, tiny distance through the air, leaving your ear canal completely unobstructed. The result is profoundly different from any other listening experience. You hear your music or call with surprising clarity, yet you also hear the world around you, entirely undiminished. It’s less like wearing headphones and more like having a personal, invisible sound system hovering just over your shoulder.

The Unseen Symphony of Enabling Tech

This experience isn’t the result of a single innovation, but a convergence of several mature technologies working in concert.

The seamlessness of the connection, for instance, is a testament to the quiet evolution of wireless standards. The mention of “Bluetooth 5.3” on a spec sheet might seem like arcane jargon, but it represents decades of refinement in radio physics. Compared to its predecessors, it creates a more robust and stable link between your device and the headphones, drastically reducing dropouts while sipping power far more efficiently. This isn’t magic; it’s the hard-won result of engineers constantly battling the fundamental trade-offs between bandwidth, range, and energy consumption.

Then there’s the question of real-world resilience. An “IPX6” rating is another piece of technical shorthand, but it tells a story of material science and meticulous engineering. The “Ingress Protection” code is a global standard that defines how well a device is sealed against foreign bodies like dust and water. The “6” here signifies protection against powerful water jets from any direction. This means the hardware can easily survive a sweaty run or a sudden rainstorm. It also means, critically, that it is not designed for submersion—a common misconception. Understanding this distinction is a small lesson in technological literacy; it’s about knowing what a tool is truly designed for.

Perhaps the most human challenge lies in ergonomics. Creating a wearable device that is comfortable and secure for millions of unique individuals is a monumental task. The featherlight weight of these devices, often around 0.63 ounces, is achieved through advanced lightweight polymers and flexible, skin-friendly silicone. Yet, user feedback for any such device will inevitably be a mix of praise for its “all-day comfort” and criticism for being “too loose.” This isn’t a failure of design, but a reflection of a fundamental truth in human factors engineering: there is no universal fit. The perfect design is a constant, delicate balancing act—a tightrope walk between security, comfort, and weight.

The Honest Acoustics of Awareness

Of course, this open-ear approach comes with an acoustic trade-off, and it’s crucial to be honest about it. Because there is no seal to trap sound, you will not get the thumping, isolating bass of a high-end over-ear headphone. Some sound will also leak out, audible to those very close to you in a quiet room.

But to call this a flaw is to miss the point entirely. It is the core feature. The goal is not to replicate the perfect fidelity of a sound-proofed studio but to create a new mode of listening. The audio quality is optimized for clarity of voice in podcasts and calls, and for the bright, energetic mid and high ranges of music that can cut through ambient noise. This is not a device for the audiophile seeking pure, analytical listening. It is for the runner who needs to hear the approaching car, the parent who needs to keep an ear out for a child while on a conference call, or the office worker who wants a soundtrack to their day without becoming oblivious to their colleagues.

It represents a paradigm shift from audio consumption as an act of exclusion to one of inclusion.

A World That Listens Back

As we move deeper into a world saturated with digital information, the debate around technology is often framed as a battle for our attention. We seek apps and devices to block out distractions and help us focus. But perhaps the answer isn’t always to build higher walls. Perhaps it’s to build smarter windows.

Open-ear audio is one such window. It allows us to be present in two worlds at once: the physical and the digital. It acknowledges that our brains are already equipped with the ultimate filtering software and that technology should work with our natural abilities, not against them.

This is a trajectory that points toward a more integrated future. This isn’t just about headphones anymore. It’s about a future where audio isn’t just for consumption, but for augmentation. Imagine a world where emerging Bluetooth standards like Auracast could broadcast museum guides, airport announcements, or conference translations directly to your open-ear device, all without making you deaf to the world around you. This is the promise of augmented reality, not in a visual, sci-fi sense, but in a practical, auditory one.

The age of the sound bubble, of deliberate sensory isolation, may be reaching its peak. The future of listening might not be about creating a more perfect escape from the world, but about finding a more elegant way to listen to our chosen soundtrack, and to the world itself, all at the same time.