The Architecture of Sound: Deconstructing the 9-Driver Hybrid IEM (Case Study: Dragonfly 81T)

Update on Nov. 23, 2025, 8:55 p.m.

In the pursuit of high-fidelity audio, there is a persistent myth: that volume equals quality. But for the audio engineer and the critical listener, the true goal is not loudness, but resolution. It is the ability to distinguish the breath of a flutist from the resonance of the room they are standing in.

Achieving this level of separation requires a shift in how we generate sound. Standard earphones rely on a single driver to do everything—a jack-of-all-trades that often masters none. To break the limitations of physics, modern high-end engineering has turned to Hybrid Architecture.

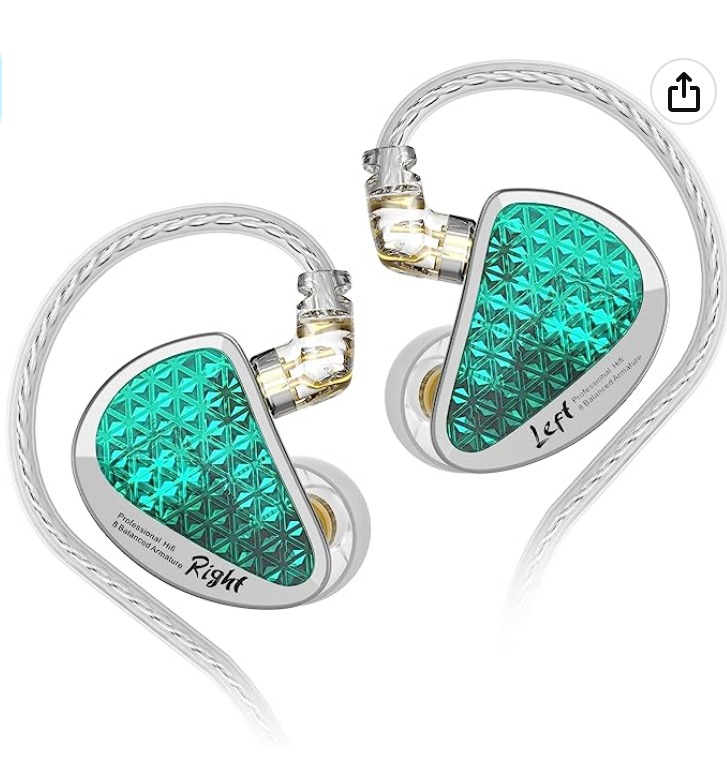

Today, we are looking under the hood of the HiFiGo Juzear Dragonfly 81T, a device that packs an astounding nine drivers per side (1DD + 8BA), to understand the complex science of building a concert hall that fits inside your ear canal.

The Challenge of Spectral Division: 1DD + 8BA Explained

Why would anyone need nine speakers in one ear? To answer this, we must look at the frequency spectrum.

A single diaphragm struggling to reproduce a 20Hz sub-bass rumble (which requires slow, heavy movement) while simultaneously playing a 15kHz cymbal crash (which requires lightning-fast vibration) often succumbs to Intermodulation Distortion. The bass physically distorts the treble.

The Dragonfly 81T solves this through extreme specialization, a configuration known as 1DD + 8BA:

- The Foundation (1 Dynamic Driver): Low frequencies are essentially moving air. The Dragonfly employs a single Dynamic Driver (DD) for this task. Like a miniature subwoofer, its larger diaphragm has the excursion capabilities needed to create the physical “slam” of a bass drum or the rumble of a synthesizer.

- The Detail (8 Balanced Armatures): Mid and high frequencies require speed, not mass. This is the domain of the Balanced Armature (BA). Originally designed for hearing aids, these tiny drivers use a magnetically balanced reed that has almost zero inertia. By deploying eight of them, engineers can assign specific clusters to specific frequency bands—vocals, upper-mids, lower-treble, and ultra-highs.

This is the audio equivalent of a relay race. Instead of one runner trying to sprint a marathon, you have nine specialists, each operating in their peak performance zone.

The Invisible Conductor: The Crossover Network

Simply stuffing nine drivers into a shell results in chaos, not music. If a bass driver tries to play vocals, or a tweeter tries to play bass, the sound becomes muddy and incoherent.

The solution is the Electronic Crossover.

Inside the Dragonfly 81T lies a complex circuit of capacitors and inductors that acts as a traffic controller. It filters the electrical signal, ensuring that: * Only low frequencies reach the Dynamic Driver. * Only mid frequencies reach the vocal BAs. * Only high frequencies reach the treble BAs.

This Phase Coherence is what creates the “holographic” 3D soundstage enthusiasts crave. When calibrated correctly, the listener stops hearing “drivers” and starts hearing instruments placed in specific locations around their head.

Signal Purity: The Science of Balanced Audio

The engineering doesn’t stop at the drivers. The signal path—how the electricity gets from your player to the earphone—is equally critical. This brings us to a feature often misunderstood by the general public: the 4.4mm Balanced Plug.

The Dragonfly 81T features a modular system allowing users to switch between a standard 3.5mm plug and a 4.4mm balanced plug. But what is the actual benefit?

It comes down to Common Mode Rejection. * Unbalanced (3.5mm): The left and right channels share a common ground wire. If this wire picks up radio interference or electrical noise, that noise enters your music. * Balanced (4.4mm): Each channel has its own dedicated positive and negative path. The amplifier sends the audio signal down one path and an inverted copy down the other. When the signal reaches the destination, the device flips the inverted signal back. Any noise that was picked up along the way (which would be present on both wires) is mathematically cancelled out.

The result is a “blacker background”—silence sounds truly silent, allowing the micro-details produced by those 8 BA drivers to shine through without a veil of electronic hiss.

Material Physics: 6N Single Crystal Copper

Even the wire itself is a subject of material science. The Dragonfly 81T utilizes a 6N Single Crystal Copper Silver-Plated Cable.

- “6N” refers to purity (99.9999% pure copper). Impurities in metal act like speed bumps for electrons, increasing resistance.

- “Single Crystal” means the copper is cast continuously to minimize grain boundaries, which are microscopic barriers that can degrade signal integrity over time.

- “Silver Plating” utilizes the Skin Effect, where high-frequency signals tend to travel on the surface of the conductor. Silver is the most conductive metal on earth, ensuring that the delicate high-frequency information (the “air” in the music) meets the least possible resistance.

Ergonomics: The Form of Function

Finally, all this technology must interface with the human body. The ear is a sensitive organ, and a heavy, poorly shaped object will ruin the listening experience regardless of sound quality.

The Dragonfly 81T’s shell is crafted from resin, weighing only 6.1 grams. This isn’t just for comfort; it’s for Acoustic Inertia. A heavy, metal shell can sometimes ring or resonate. A properly cured resin shell provides a dense, acoustically inert chamber that prevents external vibrations from coloring the sound.

Conclusion: Engineering the Invisible

The HiFiGo Juzear Dragonfly 81T is more than just a pair of earphones; it is a case study in modern acoustic engineering. It demonstrates that the path to immersive sound is paved with distinct technological choices: the specialized division of labor among drivers, the mathematical precision of crossovers, and the preservation of signal integrity through balanced transmission.

For the listener, this means the difference between simply hearing a recording and feeling the presence of the performance. It is a reminder that in the world of high fidelity, every detail—from the magnet in the driver to the plating on the wire—serves the art of sound.