The Sonic Alliance: How Hybrid Drivers in IEMs Like the PENON ORB Master Sound

Update on Aug. 4, 2025, 8:27 a.m.

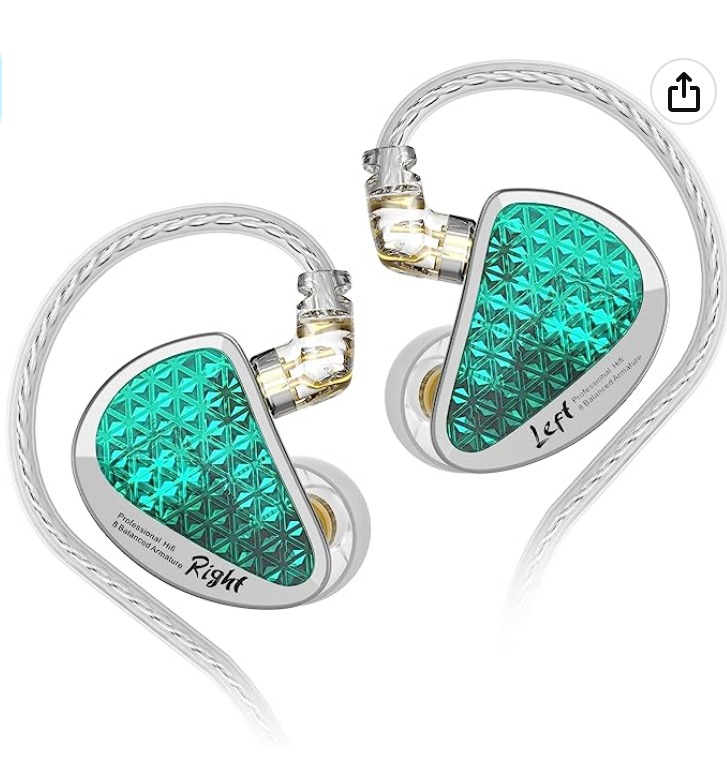

There is a modern magic we carry with us every day. It’s the paradox of holding a universe of sound within a device small enough to rest in the palm of your hand. How can the thunderous presence of a concert bass drum and the ethereal whisper of a violin string be faithfully recreated by something so small? The question is not one of magic, but of a remarkable engineering journey spanning over a century. The answer lies in a delicate partnership, a sonic alliance between two fundamentally different technologies, a fusion perfectly encapsulated in modern In-Ear Monitors (IEMs) like the PENON ORB.

To understand this alliance, we must travel back in time and meet the two titans of transduction—the process of converting electrical energy into sound.

The Two Titans of Transduction: A Tale of Two Inventions

First came the powerhouse, the ancestor of the technology most of us are familiar with: the dynamic driver. Its principle is a beautiful application of fundamental physics, tracing its lineage back to the earliest loudspeakers. Imagine a piston. An electrical audio signal flows into a coil of wire attached to a diaphragm (the piston’s surface), which is suspended in a magnetic field. This current causes the coil and the attached diaphragm to move back and forth, pushing air and creating sound waves. Its strength lies in this very action—moving a relatively large volume of air. This makes it a natural master of low frequencies, delivering the foundational weight, impact, and visceral feeling of bass that we feel as much as we hear. The 10mm dynamic driver within the ORB is a direct descendant of this legacy, tasked with providing the music’s powerful heartbeat.

But power is not everything. For the intricate details, the subtle textures of a voice or the shimmering decay of a cymbal, a different kind of specialist was needed. Its origin story is an unexpected one, born not in a concert hall, but from the necessity of clear communication. The technology of the balanced armature (BA) driver has its roots in the early telephone receivers of Alexander Graham Bell and was later miniaturized and perfected within the hearing aid industry, most notably by pioneers like Knowles.

Unlike the brute-force piston of a dynamic driver, a balanced armature is an exercise in finesse. Inside, a tiny reed (the armature) is delicately balanced within a magnetic field. The audio signal causes this armature to pivot with incredible speed and precision, and its minute movements are transferred to a diaphragm. Because the moving mass is infinitesimally small, a BA driver can respond to the subtlest electrical signals with astonishing speed. It is the precisionist, the neurosurgeon of the audio world, capturing the fine details and textures that give music its life and realism.

The Art of the Crossover: Forging a Sonic Alliance

For decades, these two technologies largely walked separate paths. You had the warmth and power of dynamic drivers or the analytical clarity of balanced armatures. The great engineering challenge was, how do you get these two fundamentally different specialists to perform as a single, coherent orchestra? How do you combine the brawn of the cello section with the dexterity of the first-chair violin?

The solution is an elegant piece of engineering known as the acoustic crossover.

An acoustic crossover is an invisible conductor. It is a set of electronic filters that directs traffic, sending the low-frequency signals (the bass and lower mids) to the dynamic driver, which is best equipped to handle them, while simultaneously routing the high-frequency signals (the upper mids and treble) to the nimble balanced armature.

This ensures that each driver operates only in its “sweet spot,” the frequency range where it is most efficient and produces the least distortion. This division of labor is critical. Without it, the result would be sonic chaos. With it, you achieve a seamless tapestry of sound, leveraging the raw power of one technology and the intricate detail of the other. For this complex system to work efficiently with any device, from a professional player to a simple smartphone, it needs to be easy to power. This is where specifications like a low impedance of $10\text{ }\Omega$ and a high sensitivity of $112\text{ dB}$ become crucial, signifying that even a small amount of power can make the internal orchestra sing loudly and clearly.

The Body for the Soul: More Than Just a Shell

The most brilliant engine is useless without a well-designed chassis. The sound created by the drivers must be delivered to the ear canal accurately, and the device itself must be comfortable and unobtrusive. Here, modern manufacturing and materials science play a starring role. The use of medical-grade resin and 3D printing has revolutionized IEM design. It allows engineers to create complex, organic shapes that mirror the intricate folds of the human ear, something impossible with traditional molding techniques.

This ergonomic form is not just for comfort; it’s a critical acoustic component. A snug fit creates a seal, providing a high degree of passive sound isolation. By physically blocking outside noise, it allows the listener to perceive the finest details in the music without having to turn up the volume to dangerous levels. The shell itself becomes a carefully tuned acoustic chamber, and the final pathway for the sound’s journey is the cable. High-purity conductors, like the silver-plated OCC (Ohno Continuous Cast) copper, are chosen for their ability to transmit the delicate audio signal with minimal loss, ensuring that the information meticulously reproduced by the drivers is the same information that left your music player.

Conclusion: The Echo of History in Your Ear

When you listen to a modern hybrid IEM, you are hearing more than just music. You are hearing the echo of a history that began with the invention of the telephone. You are experiencing the synergy of two distinct solutions to the same fundamental problem: the perfect reproduction of sound. The raw, visceral power of the dynamic driver and the analytical, detailed precision of the balanced armature, once separate philosophies, are now united in a sonic alliance.

A device like the PENON ORB is a microcosm of this journey. It stands as a testament to the relentless human desire to capture and recreate reality, from the grandest gesture to the most fleeting whisper. To understand the science within is to transform the act of listening. It is no longer just a passive experience, but an active appreciation for the century of innovation resting comfortably in your ear.