The Pursuit of Neutrality: Why "Reference" Audio Matters in a Colored World

Update on Dec. 19, 2025, 9:58 p.m.

In an age of algorithmic audio, bass-boosted profiles, and spatial simulation, the concept of “neutrality” can seem almost archaic. Modern consumer audio often strives to enhance reality—to make the explosion louder, the bass deeper, and the vocals silkier than they ever were in the studio. Yet, for a dedicated cadre of audiophiles, sound engineers, and purists, the holy grail remains unchanged: the unvarnished truth.

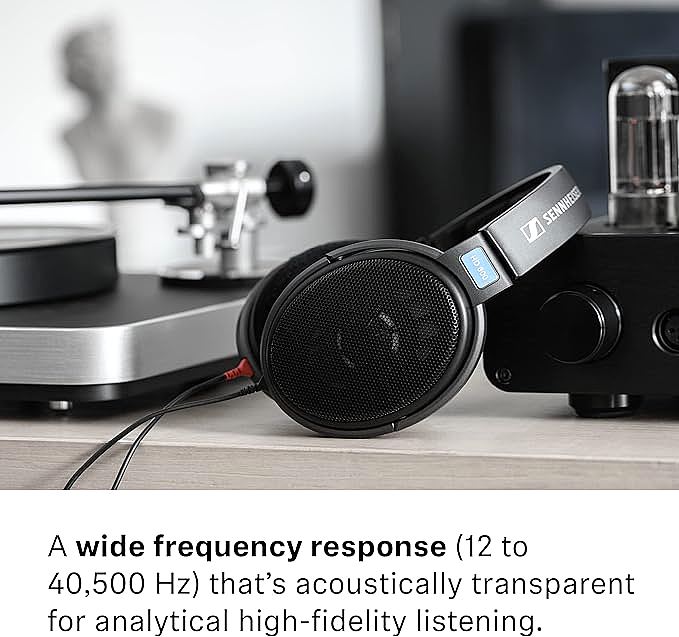

This pursuit of sonic honesty is what defines “Reference Class” audio. It is a philosophy that values transparency over excitement, and accuracy over impact. It is the reason why a headphone design from 1997, the Sennheiser HD 600, remains a benchmark in recording studios and listening rooms worldwide. To understand the endurance of such a device is to understand the fundamental difference between listening to equipment and listening to music.

The Definition of “Reference”

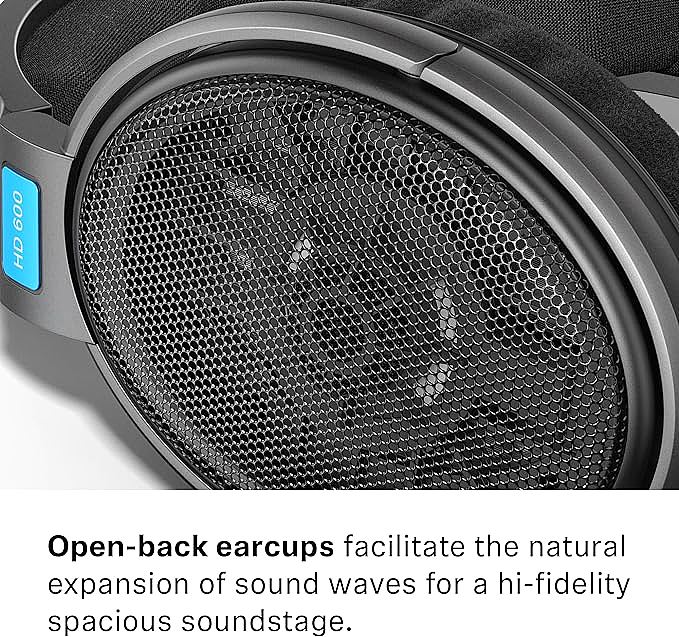

What does it mean for a headphone to be a “reference”? In scientific terms, it implies a flat frequency response. Imagine a line graph where the horizontal axis is pitch (from low bass to high treble) and the vertical axis is volume. A theoretically perfect speaker would reproduce every frequency at exactly the same volume relative to the input signal. This is “flat.”

However, human hearing is not flat—we are more sensitive to mids than bass or treble. Therefore, a reference headphone isn’t just mathematically flat; it is tuned to sound perceptually balanced to the human ear. It acts as a clear window, adding no tint (coloration) to the view. If the recording is bright, the headphone sounds bright. If the recording is muddy, the headphone sounds muddy. It is an unforgiving mirror.

The Problem with “Fun” Tuning

Most consumer headphones feature a “V-shaped” sound signature: boosted bass and boosted treble. This is the audio equivalent of adding saturation and contrast to a photo. It makes pop music sound energetic and movies feel immersive. But for critical listening, this “fun” tuning is a liability. It masks details in the midrange—where vocals and most acoustic instruments live—and fatigues the ear over time.

Reference headphones like the HD 600 take the opposite approach. They champion the midrange. By stripping away the artificial bass bloat and treble spike, they reveal the texture of the voice, the resin on the violin bow, and the decay of the reverb tail. This is not about being boring; it is about being faithful.

The Midrange: The Heart of Music

The human evolutionary imperative has tuned our ears to be hyper-sensitive to the frequency range of the human voice (roughly 300Hz to 3000Hz). This is where communication happens. Consequently, this is where the emotional core of music resides.

Reference headphones are often defined by their “mid-forward” presentation. This means they prioritize the clarity and naturalism of this crucial band. When you listen to a vocal track on a V-shaped headphone, the singer might sound distant or recessed behind the bass line. On a reference set, the singer steps forward, occupying the center stage. This intimacy is what audiophiles describe as the “veil being lifted.”

The Tool of the Trade: Why Engineers Need Honesty

For a mixing or mastering engineer, headphones are a diagnostic tool. If an engineer mixes a track using headphones with boosted bass, they will likely turn the bass down in the mix to compensate. When that track is played on a neutral system, it will sound thin and weak.

Conversely, if they mix on a neutral reference like the Sennheiser HD 600, they can trust that their decisions will translate well across different playback systems—from car stereos to club speakers. The 300-ohm impedance and lightweight aluminum voice coils of such headphones are not just specs; they are engineered to provide the precise transient response needed to hear micro-dynamics. Engineers need to hear the start and stop of every note with absolute precision to set compression and gate levels correctly.

The Audiophile’s Journey: Learning to Listen

Transitioning from consumer audio to reference audio is a journey of re-education. At first, a neutral headphone might sound “light” on bass or “dry.” This is because the listener has been conditioned to expect the artificial thump of enhanced bass.

However, as the ear adjusts (a process known as “burn-in” of the brain, not the driver), the listener begins to appreciate what was previously hidden. They start to hear the separation between instruments. They notice that the bass, while not earth-shattering, is tight, textured, and melodic. They realize that the “dryness” is actually the absence of distortion and resonance.

This appreciation for neutrality is often the endpoint of the audiophile hobby. After cycling through headphones that offer “liquid mids” or “slamming bass,” many enthusiasts return to the neutral reference. They realize that the best flavor is no flavor at all. They want to hear the recording, not the headphone.

Conclusion: The Timelessness of Truth

Technology evolves. Bluetooth codecs improve, battery life extends, and noise cancellation becomes smarter. But the physics of sound and the biology of human hearing remain constant. This is why a reference headphone design can endure for decades without obsolescence.

The Sennheiser HD 600 serves as a reminder that in a world of constant digital enhancement, there is immense value in analog honesty. Whether you are a professional ensuring a mix translates to the world, or a music lover wanting to hear exactly what the artist intended, the pursuit of neutrality is not just technical—it is an act of respect for the art of sound.