The Hybrid Engine: Physics of Dynamic and Balanced Armature Drivers

Update on Dec. 31, 2025, 8:12 p.m.

In the wireless age, where convenience often trumps fidelity, the wired In-Ear Monitor (IEM) stands as a bastion of pure audio engineering. It is a device unencumbered by batteries, Bluetooth chips, or compression algorithms. Its sole purpose is to convert an analog electrical signal into sound waves with the highest possible precision.

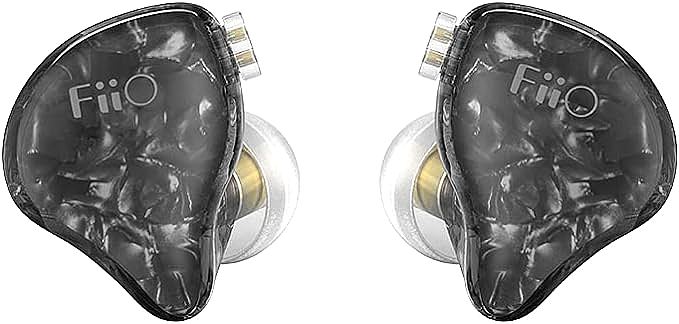

The FiiO FH1s represents a classic architectural choice in this domain: the Hybrid Driver System. By combining a massive 13.6mm dynamic driver with a precision Knowles balanced armature, it attempts to marry the visceral impact of a loudspeaker with the clinical detail of a hearing aid. This article deconstructs the physics of these two disparate technologies and explores the engineering challenge of making them sing in harmony.

The Foundation: 13.6mm Dynamic Driver Physics

The “DD” (Dynamic Driver) is the workhorse of the audio world. Its principle is electromagnetic induction, discovered by Faraday.

1. Voice Coil: A coil of wire is attached to a diaphragm.

2. Magnetic Field: This coil is suspended in a magnetic gap.

3. Movement: Current flows through the coil, creating a magnetic field that interacts with the permanent magnet, pushing the diaphragm back and forth.

The Physics of Diameter

The FH1s uses a 13.6mm driver. In the world of IEMs, where 6mm to 10mm is standard, 13.6mm is enormous.

* Air Displacement ($V_d$): To reproduce low frequencies (bass), a driver must move a large volume of air.

$$V_d = Area \times Excursion$$

A 13.6mm driver has nearly twice the surface area of a 10mm driver. This means it can move the same amount of air with half the excursion. Less excursion means the voice coil stays within the most linear part of the magnetic field, significantly reducing Total Harmonic Distortion (THD) at low frequencies.

* Biocellulose/Polymer Diaphragm: The description mentions a “polymer diaphragm.” In large drivers, diaphragm rigidity is crucial to prevent “cone breakup” (where the diaphragm wobbles instead of moving as a piston). FiiO’s choice of material likely balances stiffness with internal damping, ensuring that the “Robust Bass” is tight and controlled, not flabby.

The Detail Merchant: Knowles Balanced Armature

While the dynamic driver handles the heavy lifting of bass and lower mids, the FH1s hands off the baton to a Balanced Armature (BA) driver for the highs. The specific unit used is the Knowles 33518.

The Mechanics of Balance

Unlike a dynamic driver, a BA driver does not have a coil attached to the diaphragm.

1. The Armature: A tiny metal reed (armature) is balanced between two magnets inside a stationary coil.

2. The Pivot: When the coil is energized, the armature pivots.

3. The Drive Rod: This microscopic motion is transferred via a rod to a stiff aluminum diaphragm.

Transient Response

The key advantage of the BA is mass. The moving parts are incredibly light. This gives the BA driver exceptional transient response—it can start and stop moving almost instantly. * High Frequency Reproduction: This speed allows the BA to trace the rapid waveforms of high-frequency sounds (cymbals, violins) with a precision that a heavy dynamic driver cannot match. * Placement: The Knowles 33518 is placed directly in the sound nozzle, closer to the ear drum. This minimizes the loss of high frequencies, which are easily absorbed by air and tube walls. This proximity creates the “sense of realism and tactility” in the treble.

The Marriage of opposites: The Crossover Network

We have a beast (13.6mm DD) and a scalpel (Knowles BA). If connected directly to the source, they would overlap and clash. The dynamic driver would try to play treble (poorly), and the BA would try to play bass (and likely distort).

The solution is the Crossover.

* Low-Pass Filter: A circuit (likely an inductor) that allows low frequencies to pass to the dynamic driver but blocks highs.

* High-Pass Filter: A circuit (likely a capacitor) that allows high frequencies to pass to the BA driver but blocks lows.

Phase Coherence

The engineering challenge in a hybrid IEM like the FH1s is Phase Alignment. The dynamic driver is deep in the shell; the BA is in the nozzle. Sound from the DD takes longer to reach the ear than sound from the BA.

FiiO’s acoustic engineers must tune the crossover and the physical positioning so that the sound waves from both drivers arrive at the ear drum at the exact same time. If they are out of phase, you get “cancellation dips” in the frequency response. The “classic balanced sound” of the FH1s suggests a successful integration where the listener hears a unified whole, not two separate drivers.

Acoustic Pressure Balancing

A large dynamic driver moving a lot of air creates pressure waves not just towards the ear, but also back into the shell. If this pressure is trapped, it acts as an air spring, restricting the driver’s movement (damping).

The FH1s features “Dynamic airflow balance technology.” This likely involves carefully calculated vents.

* Front Vent: Relieves pressure in the ear canal, preventing “driver flex” (crinkle sound) upon insertion and reducing listening fatigue.

* Rear Vent: Allows the space behind the driver to breathe. This lowers the resonant frequency of the system, allowing the driver to extend deeper into the sub-bass region. It effectively tunes the “enclosure” of the speaker.

Conclusion: The Best of Both Worlds

The FiiO FH1s is a testament to the “Hybrid Theory” of audio. It acknowledges that no single driver type is perfect. By assigning the bass to a massive dynamic driver and the treble to a nimble balanced armature, it leverages the physics of each technology.

For the budget audiophile, this architecture offers a glimpse into high-end sound. It provides the rumble of a subwoofer and the clarity of a tweeter in a package that fits in your pocket. It is engineering rigor applied to the pursuit of musical emotion.