The Architecture of Sound: How a Simple Earphone Like the Betron AX1 Creates Your Private Universe

Update on July 1, 2025, 9:25 a.m.

The world is a loud place. Imagine standing on a subway platform, a cacophony of screeching wheels, overlapping announcements, and the dull roar of a hundred conversations washing over you. It’s a chaotic flood of sound. Then, you perform a small, almost ritualistic act. You unspool a pair of simple wired earphones, place the buds in your ears, and press play. In an instant, the world vanishes. The screeching train becomes a distant echo, the roar of the crowd fades to a whisper, and you are suddenly alone, standing in the center of your own private universe of sound.

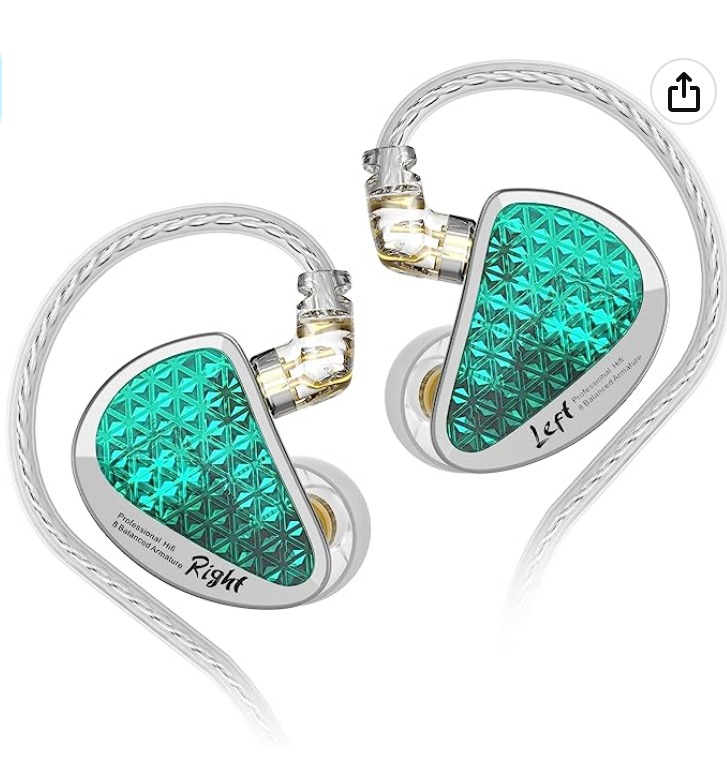

How does this happen? How can two tiny objects, connected by a mere wire, perform such a potent act of alchemy, transforming a chaotic public space into an intimate concert hall? It’s not magic. It’s a feat of engineering, a discipline we might call the architecture of sound. Using a humble product like the Betron AX1 Wired In-Ear Headphones as our blueprint, we can explore how, piece by piece, this personal sanctuary is built.

The Foundation: Walls of Silence Born on Stage

Before we can build up, we must first wall off. The most critical feature of any in-ear earphone is its ability to isolate you from the outside world. This concept of a personal sound seal has a surprisingly rebellious rock-and-roll origin. In 1995, frustrated by the deafening volume of on-stage monitors that made it impossible to hear his own bandmates, Van Halen’s drummer, Alex Van Halen, collaborated with an audio engineer named Jerry Harvey. The solution they devised was the first custom-fitted In-Ear Monitor (IEM). It was a revolutionary idea: instead of trying to out-volume the noise, they would block it out entirely.

The Betron AX1, like all modern in-ear headphones, is a direct descendant of that stage-born innovation. Its effectiveness begins with passive noise isolation. By selecting the correct size of silicone ear tip, you create a physical seal in your ear canal. This seal acts as the foundation of our sound architecture—a simple, yet profoundly effective wall that physically blocks a significant portion of high-frequency ambient noise. It’s the architectural equivalent of closing a heavy door on a noisy street, allowing the space inside to become a blank canvas for sound.

The Pillars and Beams: The Engine of Emotion

With our foundation of silence laid, we can erect the pillars that will support the entire structure of our music. Inside each earphone is an 8mm dynamic driver, the veritable engine of emotion. This is where electricity is transmuted into sound. But simply making noise is easy; making it feel real is the challenge.

The specification sheet tells us the driver covers a 20Hz to 20,000Hz frequency range. To an engineer, this is the full spectrum of human hearing. Think of it as a master painter’s palette. 20Hz is the deep, sub-bass rumble you feel in your chest at a concert, the darkest indigo on the canvas. 20,000Hz is the airy, crystalline shimmer of a brushed cymbal, the brightest, most brilliant white. A driver capable of reproducing this entire range has all the colors needed to paint a complete and vivid musical picture.

However, having the colors is not enough; a master architect must know how to balance them. Here we encounter a secret blueprint of audio science known as the Fletcher-Munson curves. This research from the 1930s demonstrated that our ears’ sensitivity to different frequencies changes dramatically with volume. At low volumes, we are much less sensitive to low and high frequencies. This is why achieving a “balanced sound”—one that feels natural and full at both a whisper and a roar—is a true engineering art. It requires careful tuning of the driver and the chamber it sits in.

Furthermore, our structure must be energy-efficient. The AX1’s 16 Ohm impedance means it requires very little power to operate. In architectural terms, its pillars are light but strong, perfectly designed to be supported by the modest power output of a smartphone or laptop, without needing a massive, external power station (or amplifier).

The Concert Hall’s Walls: The Magic of the Chamber

Every great concert hall, from Carnegie Hall to the Sydney Opera House, is defined by its walls. The materials used, their shape, and their rigidity dictate how sound waves reflect and decay, creating the hall’s unique acoustic signature. An earphone is no different; its housing is its own miniature concert hall.

The AX1 is constructed from lightweight aluminum housing. This choice is not merely for a premium feel or durability. It is a critical acoustic decision. Cheaper plastic housings are prone to flex and vibrate along with the music, creating their own unwanted resonances. It’s like listening to a concert in a hall with rattling windowpanes—the unwanted noise colors and muddies the original performance. The rigidity of aluminum, however, creates an inert and stable chamber. It acts like the dense, non-resonant walls of a professional recording studio, ensuring that the only vibrations reaching your ear are the ones created by the driver itself. The result is a cleaner, purer sound, free from the distortion of a poorly constructed room.

The Golden Gate: A Legacy of Connection

Our sonic architecture needs a reliable entrance. The signal, carrying the soul of the music, must travel from your device into the structure without being corrupted. This journey is made possible by one of the most enduring and reliable standards in audio history: the 3.5mm jack. Tracing its lineage back to 19th-century telephone switchboards, this humble connector became a global icon with the Sony Walkman. Its beauty lies in its simplicity and robustness.

On the AX1, this connector is gold-plated. Again, this is not a luxury affectation. Gold is a noble metal, meaning it is exceptionally resistant to corrosion and oxidation. Over time, lesser metals can tarnish, creating a microscopic layer of electrical resistance that can degrade the audio signal, introducing static or weakening the connection. The gold plating acts as a perpetually clean, unblemished gateway. It is the guarantee that the intricate electrical language of the music arrives at the driver’s doorstep exactly as it was sent, ready to be translated into sound.

The Interior Furnishings: The Thoughtful Details of Living

A building is not a home until it is furnished. The final touches of our sound architecture are the details that transform it from a functional structure into a comfortable, livable space. The tangle-free cable is a small triumph of material science, designed to resist the entropy of your pocket. The in-line microphone turns your private concert hall into a communication hub. The multiple sizes of ear tips are the equivalent of custom-fitted furniture, ensuring the space is perfectly tailored to you. These are not headline features, but they are a testament to a design philosophy that considers the entire user experience.

Conclusion: An Architectural Beauty, Accessible to All

As we stand back and admire our completed structure, a powerful idea comes into focus. The Betron AX1, and products like it, are not remarkable because they contain some rare, exotic technology. They are remarkable because they demonstrate a profound respect for the fundamental principles of physics, acoustics, and engineering. They prove that a beautiful space for sound does not require the most expensive materials, but rather the most intelligent design.

By understanding the architecture of sound—the foundational seal against noise, the carefully balanced pillars of frequency, the solid walls of the acoustic chamber, and the ever-reliable golden gate—we can appreciate that a great listening experience is not a luxury. It is a form of elegant problem-solving. It is a testament to the idea that the beauty of science and engineering, when applied with thought and care, can and should be accessible to everyone.