TOZO NC2 Wireless Earbuds: Silence the World with Advanced Noise Cancellation

Update on Sept. 23, 2025, 9:40 a.m.

It began, for me, at 30,000 feet, somewhere over the Atlantic. The world was a relentless, soul-shaking roar. The deep, bone-rattling hum of the Rolls-Royce engines was not merely a sound but a physical presence, a constant pressure on the skull. Then, a click. I put on a pair of inexpensive noise-canceling earbuds, and the world fell away. The roar collapsed into a distant, harmless whisper. It wasn’t just quiet. It was an impossible, artificial calm. A silence that hadn’t existed in that space a moment before.

In that instant, I realized I hadn’t just purchased a piece of consumer electronics. I had purchased a programmable slice of reality. I had bought silence.

We tend to think of silence as a natural state, a simple absence of sound. But in our modern world, true silence is a rare luxury. What we experienced in that airplane cabin, and what millions of us now experience daily in open-plan offices and rattling subway cars, is something else entirely. It is an engineered silence. It is the product of a century-long quest to not just block noise, but to actively erase it from existence. And the key to this technological magic lies in a beautifully elegant principle of physics.

Inventing the Anti-Sound

To understand how to destroy a sound, you must first understand its nature. Sound is a pressure wave, a vibration rippling through the air. Like ripples in a pond, these waves have crests (compressions) and troughs (rarefactions). For most of history, our only defense against unwanted waves was a solid wall—muffling, not eliminating. But in the 1930s, a German physicist named Paul Lueg filed a patent for a radical idea: what if you could fight a wave with another wave?

The principle is called destructive interference. Imagine sending a perfect “anti-ripple” across that pond to meet the first one. This anti-ripple has a trough wherever the original has a crest, and a crest wherever the original has a trough. When they meet, they perfectly annihilate each other. The water becomes flat.

This is precisely what Active Noise Cancellation (ANC) does. It doesn’t block sound; it creates anti-sound. The journey from Lueg’s patent to the earbuds in your pocket was long and arduous, driven by the high-stakes need of aviators to hear radio communications over the roar of their own engines. Early systems developed by engineers like Lawrence Fogel in the 1950s were bulky, analog, and power-hungry. The revolution came with the miniaturization of microphones and the rise of the Digital Signal Processor (DSP)—a tiny computer dedicated to a single task.

Consider a modern, budget-friendly device like the TOZO NC2 earbuds. It serves as a perfect microcosm of this history. It employs a sophisticated hybrid ANC system. A microphone on the outside listens to the world, identifying the relentless, low-frequency hum of an engine or an air conditioner. A second microphone on the inside listens for any sound that leaks through, acting as a quality-control check. The DSP then takes this information and, thousands of times per second, generates a precise, inverted soundwave. The manufacturer claims a noise reduction of over 35 decibels ($35dB$)—a logarithmic scale on which every 10dB reduction represents a tenfold decrease in sound intensity. It’s the digital fulfillment of Lueg’s analog dream.

The Photoshop for Your Ears

But the technology didn’t stop at deletion. If you can use microphones and processors to subtract reality, you can also use them to add to it, or even to reshape it. This is where we move from mere noise cancellation into the realm of editing our auditory world.

Most modern ANC headphones feature a “Transparency Mode.” With a tap, the very same microphones used to identify noise are repurposed. They capture the outside world—a flight attendant’s announcement, an approaching car, a colleague’s question—and pipe it directly into your ears. It is an audio pass-through, a digitally augmented layer of hearing. You are no longer just a passive recipient of sound; you are the mixer at the board, deciding which channels to mute and which to amplify.

This editing goes deeper, into the very character of the sound you do choose to hear. If you’ve ever found the sound from consumer headphones to be particularly bass-heavy, you’re not imagining things. This isn’t a flaw; it’s a deliberate choice rooted in psychoacoustics, the science of how we subjectively perceive sound. Our hearing is not a faithful, linear recording device. The Fletcher-Munson curves, for instance, show that at lower volumes, our ears are far less sensitive to low and high frequencies than they are to the midrange, where human speech resides. To make music sound “rich” and “full” at a normal listening level, engineers often boost the bass and treble to compensate for our own perceptual biases. The tuning of the NC2, with its prominent bass, isn’t aiming for physical accuracy; it’s aiming for a perception that feels right to the majority of listeners. It is, in essence, an Instagram filter for your music.

The Fine Print of a Programmable Reality

Of course, this power to edit reality comes with compromises, especially when it’s delivered at a consumer price point. These trade-offs are a fascinating lesson in modern engineering. The promise of Bluetooth 5.2, for example, is a faster, more stable connection with lower latency. Yet, anyone who has watched a video with wireless headphones has likely noticed a slight, maddening mismatch between a speaker’s lips and their words. The bottleneck isn’t just the Bluetooth version; it’s a complex chain of software codecs (the compression algorithms like SBC and AAC that the NC2 supports), the phone’s processing power, and the earbud’s own internal hardware.

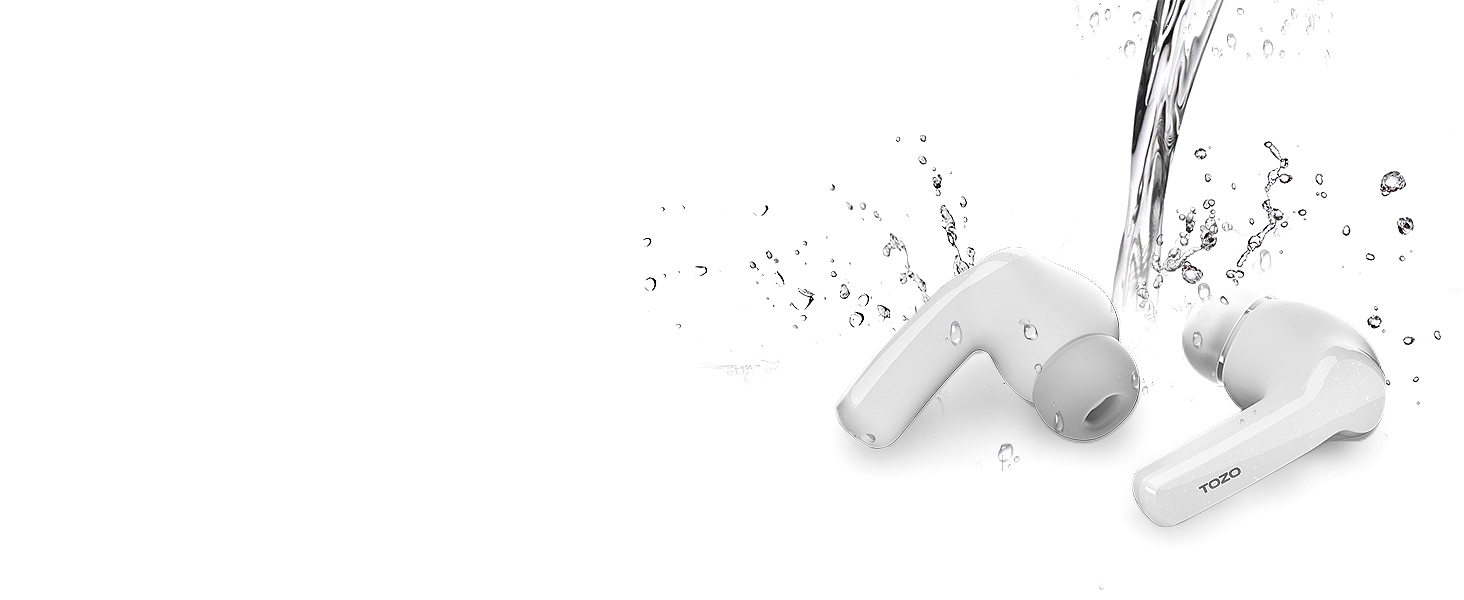

This gap between marketing promise and lived experience is common. Some third-party reviews of the NC2 noted that their unit lacked the advertised wireless charging capability—a likely inconsistency in manufacturing batches. Its IPX6 rating means it can withstand a powerful jet of water, a testament to clever engineering with hydrophobic coatings and seals, yet waterproofing an acoustic device that must, by definition, be open to the air is a constant battle.

These aren’t failures so much as they are the fine print of our new reality. We have been given god-like tools to manipulate our sensory input, but they are built by mortals, constrained by budgets and the stubborn laws of physics.

We are at the very beginning of this era of programmable perception. The same earbuds that cancel noise today may monitor our heart rate tomorrow, translate languages in real-time, or subtly enhance the sounds we want to hear while filtering out the rest. We have taken one of our fundamental senses and made it subject to digital control. The question we must now ask ourselves is a profound one: In our quest to perfect the soundtrack of our lives, what parts of the messy, authentic, and unedited world are we choosing to tune out?