From Code to Crescendo: The Unheard Story of Your Headphones

Update on July 24, 2025, 3:22 p.m.

There is a universal magic in the simple act of putting on a pair of headphones. The chaotic symphony of the outside world—the traffic, the chatter, the hum of fluorescent lights—fades into a gentle murmur. In its place, the opening chords of a favorite song bloom into existence, creating an intimate bubble of sound just for you. It’s a personal concert, a private sanctuary. But have you ever paused, in the quiet space between tracks, to wonder about the century of innovation nestled over your ears? How does this simple object perform such a profound act of alchemy, turning silent electricity into pure emotion?

The story doesn’t begin in a gleaming Silicon Valley lab or a Tokyo design studio. It starts, improbably, at a kitchen table in Utah in the early 1900s. There, an inventor named Nathaniel Baldwin, tinkering with compressed air and levers, cobbled together a device for the United States Navy. His creation wasn’t designed for music; its purpose was far more austere. It was built to amplify the faint, rhythmic clicks of Morse code, translating vital communications directly to an operator’s ears. These first headphones were a tool of war and industry, born from a need for clarity amidst the noise. The idea of personal audio was born not for entertainment, but for utility.

For decades, headphones remained in the realm of professionals: aviators, radio operators, and switchboard attendants. The sound was functional, often tinny and presented in monaural—the same signal in both ears. The revolution, the moment headphones pivoted towards pleasure, arrived in 1958. It was then that John C. Koss introduced the world to the Koss SP/3, the first commercially successful stereophonic headphones. Suddenly, sound had dimension. Music could be panned from left to right, creating a sense of space and immersion that was previously only possible with a room full of speakers. Yet, it was the arrival of the Sony Walkman in 1979 that truly democratized the experience, untethering high-fidelity music from the living room and turning the entire world into a potential concert hall. The small, portable cassette player and its lightweight headphones sparked a cultural phenomenon, creating the personal sound bubble we now take for granted.

The Unseen Engine: How Electricity Becomes Emotion

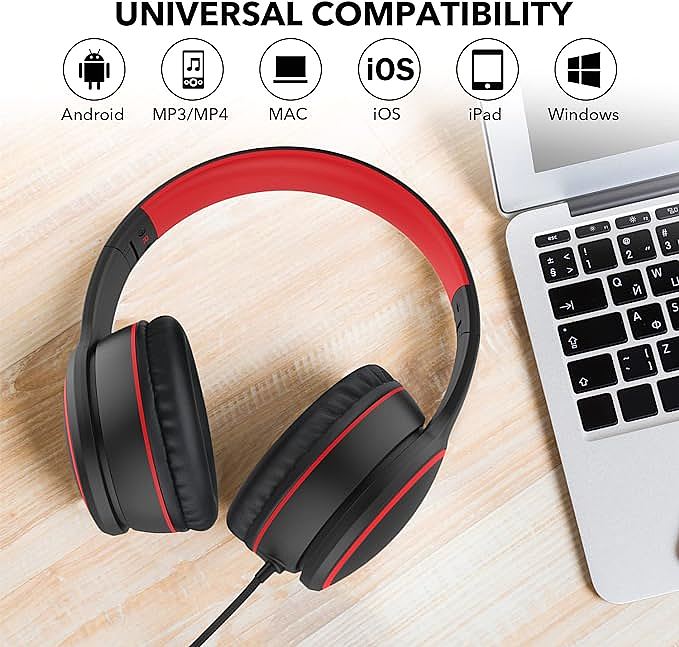

Every time you listen, you are witnessing a marvel of physics taking place within that unassuming shell. The heart of most headphones, from vintage sets to a modern pair like the RORSOU R10 On-Ear Headphones, is a technology known as the dynamic driver. Think of it as a perfect, miniature loudspeaker, engineered to perform for an audience of one.

Its operation is an elegant dance of electricity and magnetism. An audio signal, which is essentially a complex electrical current, flows from your device into a tiny, tightly-wound voice coil. This coil is attached to a thin, flexible membrane called a diaphragm and is suspended within the field of a powerful, permanent magnet. As the electrical current of your music surges and recedes through the coil, it generates a fluctuating magnetic field. This field pushes and pulls against the permanent magnet, causing the coil—and the diaphragm attached to it—to vibrate thousands of times per second. This vibration is what displaces the air, creating the precise pressure waves that your eardrum captures and your brain deciphers as a soaring vocal, a crisp cymbal crash, or a deep bass line.

The physical size of this driver matters. The RORSOU R10, for example, uses 40mm drivers. A larger diaphragm has more surface area, allowing it to push a greater volume of air with each vibration. This is particularly advantageous for reproducing low-frequency sounds, which require moving more air to be perceived with richness and depth. The satisfying thump of a bass drum you feel in your chest is, in essence, what a larger driver capably recreates inches from your ear.

The Enduring Connection: A Defense of the Humble Wire

In our rush toward a wireless future, it’s easy to dismiss the simple cord as a relic. Yet, the wired connection of the R10, terminating in the resilient 3.5mm jack, holds steadfast advantages rooted in pure physics. This connector, a design that has been in use for over a century, provides a direct, unadulterated pathway for sound.

Unlike wireless Bluetooth transmission, which must compress audio data to send it through the air, a wire sends the electrical signal in its complete, uncompromised form. There is no digital compression that might strip away subtle details, no potential for wireless interference, and absolutely zero latency—the audio is instantaneous. Furthermore, it requires no internal battery, drawing its modest power needs directly from the device it’s plugged into. The R10’s 1.5M nylon-braided cord is a modern acknowledgment of this enduring utility, built for durability in a world of planned obsolescence.

Designing for Humans: The Art of Wearing Sound

A headphone is more than its internal components; it is an object that must coexist with the human body, sometimes for hours on end. This is the science of ergonomics. The R10’s on-ear design is a classic compromise, balancing the portability of smaller earbuds with the immersive quality of larger, over-ear models that fully enclose the ear.

The foam earpads perform a dual function. First, they provide comfort. But second, they create a physical seal against the ear, providing passive noise isolation. This isn’t the battery-powered, phase-canceling magic of Active Noise Cancellation (ANC), but a simple, physical barrier that dampens ambient noise. This allows you to listen at a lower, safer volume, protecting your hearing. Comfort is also a function of weight. At a mere 7.6 ounces, the R10 is designed to be light enough to almost disappear during use, preventing the neck fatigue that can come with heavier headsets.

The Echo of Innovation

So the next time you slip on your headphones, take a moment. Recognize that in that simple act, you are connecting to a long and fascinating history. The device on your head is a direct descendant of Nathaniel Baldwin’s kitchen-table invention, carrying the DNA of Koss’s stereo vision and the rebellious freedom of the Walkman. A product like the RORSOU R10 is remarkable not for being revolutionary, but for making the fruits of that revolution—clear, personal, high-fidelity sound—accessible to nearly everyone. To understand the journey of this technology, from coded signals to soaring crescendos, is to hear your favorite music with new ears, appreciating not just the art of the song, but the quiet art of the device that delivers it.