Breaking the Aquatic Silence: The Physics of Sound Transmission Beneath the Surface

Update on Nov. 23, 2025, 7:46 a.m.

For the human body, water is an alien environment. Our senses, evolved for terrestrial life, function differently the moment we submerge. Light refracts, gravity shifts, and sound—our primary anchor to reality—becomes a muffled, distorted echo. For decades, swimmers and aquatic athletes accepted this silence as the price of entry.

Bringing high-fidelity audio into this hostile environment requires solving two fundamental engineering problems: How do you transmit sound waves without air? And how do you maintain a wireless connection in a medium that actively destroys radio signals?

To understand the solutions, we must examine the intersection of biology and physics, looking at devices like the H2O Audio SONAR not merely as accessories, but as studies in acoustic adaptation.

The Bypass Road: Bone Conduction Mechanics

Traditional hearing relies on air conduction. Sound waves travel through the ear canal, vibrating the eardrum (tympanic membrane). Underwater, this system fails. Water floods the ear canal, increasing resistance against the eardrum, or earplugs block the canal entirely, leaving you with nothing but the sound of your own breathing.

Bone conduction offers an elegant bypass. It ignores the outer and middle ear entirely. Transducers, like those found on the SONAR, rest on the zygomatic bones (cheekbones). They convert digital audio signals into mechanical vibrations. These vibrations propagate through the dense bone of the skull directly to the cochlea—the fluid-filled spiral in the inner ear responsible for translating vibrations into neural impulses.

Interestingly, this method is often more effective underwater than in air. Because the human body (and the cochlea fluid) has a density closer to water than air, the acoustic impedance mismatch is reduced. This allows for a surprisingly clear transmission of frequencies that would otherwise be lost in the turbulence of a swim stroke.

The Faraday Cage Effect: Why Bluetooth Drowns

The most common frustration for modern swimmers is the failure of their waterproof smartwatches to stream music to their waterproof headphones. Both devices work perfectly on land, but the connection severs the moment they dip below the surface.

This is not a hardware failure; it is basic physics. Bluetooth operates at 2.4 GHz, a microwave frequency. Water molecules are resonant at frequencies close to this band, meaning they are exceptionally good at absorbing this energy (this is, incidentally, how microwave ovens heat food).

In a swimming pool, the water acts as a massive signal dampener. A Bluetooth signal that travels 30 feet in air struggles to travel 3 inches underwater. This necessitates a shift in device architecture. The SONAR addresses this by integrating a dedicated MP3 player with 8GB of local storage. While streaming is convenient on land, local storage is a hydrodynamic necessity. It eliminates the variable of signal loss, ensuring the data source is physically wired to the transducer, immune to the RF-absorbing medium surrounding the swimmer.

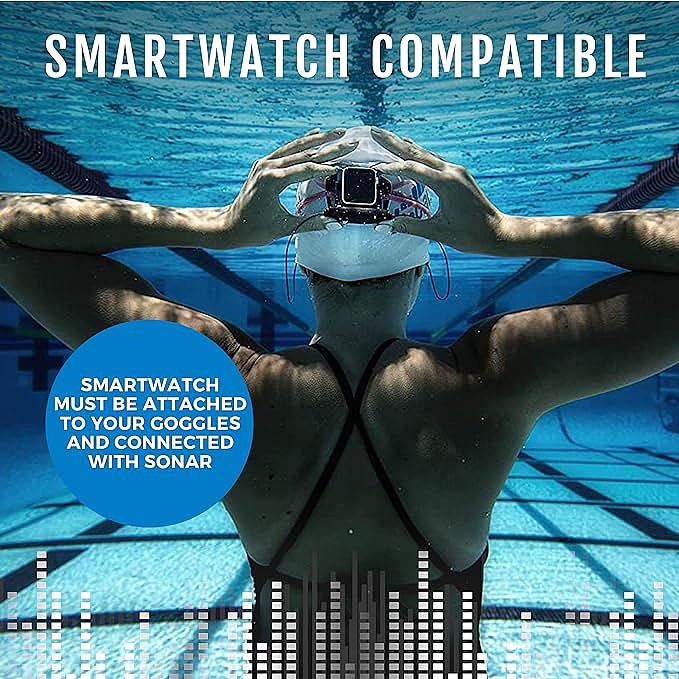

Note: The SONAR does include Bluetooth functionality, but as the physics dictates, it is effective only when the transmitting device (like a smartwatch) is clipped directly to the goggles, keeping the range within the minimal effective radius.

Hydrodynamics and The “Goggle Anchor”

On land, headphones rely on gravity and friction to stay in place. In water, they must contend with drag and turbulence. A swimmer pushing off a wall creates significant hydrodynamic force. Traditional ear-hook designs often flutter or dislodge under this pressure.

The engineering solution seen in specialized equipment is integration with existing gear. By utilizing an integrated clip design that attaches directly to the swim goggle straps, the device effectively becomes part of the swimmer’s streamlined profile. This “parasitic attachment” strategy reduces drag and ensures that the bone conduction pads maintain constant, firm pressure against the skull—a critical requirement for consistent sound transmission. If the contact loosens for even a fraction of a second, the audio coupling is broken.

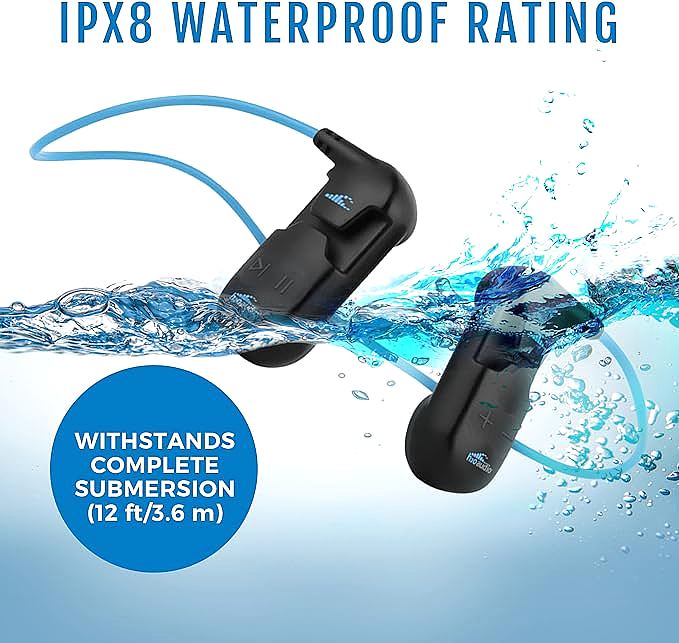

Defining IPX8: The Pressure Test

Waterproofing is not a binary state; it is a gradient of pressure resistance. The Ingress Protection (IP) scale measures this. While IPX7 allows for temporary submersion (1 meter for 30 minutes), it is insufficient for the sustained, repetitive pressure cycles of lap swimming.

IPX8, the rating carried by the SONAR, indicates protection against continuous immersion beyond 1 meter. In this specific case, up to 12 feet (3 meters). Achieving this requires more than just tight seams. It often involves: * Hydrophobic Nano-coatings: Treating internal circuitry to repel moisture even if microscopic ingress occurs. * Inductive or Sealed Charging: Removing open ports (like USB-C) which are prime failure points. The SONAR uses a specific 4-pin charging interface to maintain the integrity of the seal. * Corrosion Resistance: Using materials that can withstand not just water, but the corrosive nature of chlorine and salt.

Conclusion: Adapting to the Environment

The underwater world demands adaptation. Just as marine mammals evolved distinct physiological traits to thrive beneath the waves, our technology must undergo a similar transformation.

Devices like the H2O Audio SONAR represent this technological evolution. They strip away the reliance on air conduction and 2.4GHz radio waves, replacing them with bone conduction and local storage. They trade the convenience of streaming for the reliability of physics-compliant engineering. For the swimmer, this means the silence is finally optional, replaced by a personal soundtrack that moves as fluidly as they do.