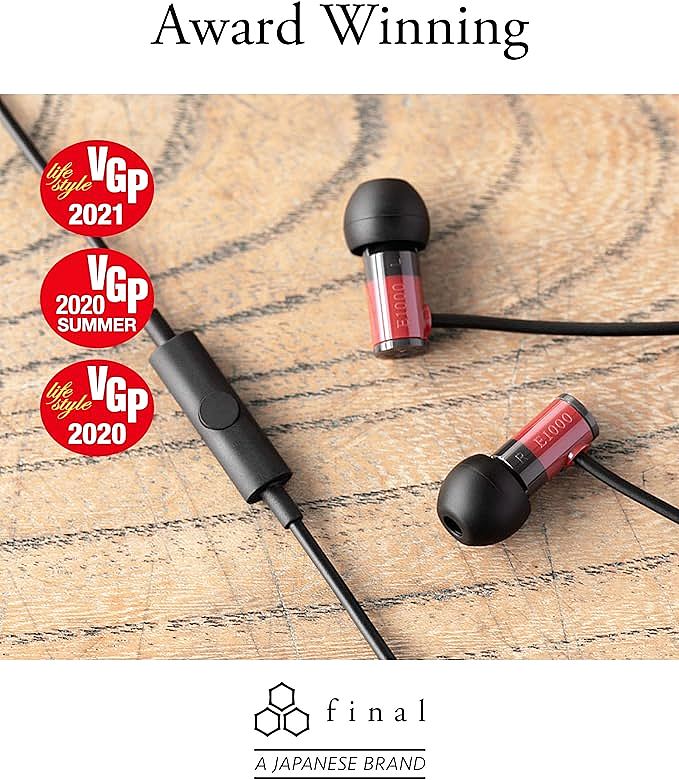

Final E1000C in-Ear Isolating Earphones: A Budget-Friendly Audio Delight Designed in Japan

Update on June 26, 2025, 7:10 p.m.

In a world saturated with audio products, we’ve been trained by marketing to equate price with performance. A higher price tag promises deeper bass, crisper highs, and a more “immersive” experience. So when a product like the Final E1000C appears, an in-ear earphone lauded with awards and a “Designed in Japan” pedigree, yet priced under forty dollars, it presents a puzzle. It seems to defy the established rules. Is it a fluke? A marketing gimmick? Or is it a quiet lesson in the art and science of engineering?

This isn’t a review. It’s an investigation. As an audio engineer, I see products like this not as magic boxes, but as a series of deliberate decisions—a symphony of carefully calculated trade-offs. The genius of a great budget product isn’t found in exotic materials or groundbreaking, singular technologies. It’s found in the masterful understanding of physics and the wisdom of knowing what to prioritize, and what to sacrifice. Let’s pop the hood and see how this remarkable machine is built.

The Engine Bay: In Pursuit of Agility, Not Brute Force

At the heart of any earphone lies its driver. The E1000C uses a single 6.4mm dynamic driver. Think of this as the engine. In the automotive world, you have choices: a massive, torque-heavy V8 or a smaller, high-revving four-cylinder. The V8 delivers earth-shaking power, a visceral, chest-thumping experience. The smaller engine, however, is lighter and more responsive. It can change speeds in the blink of an eye, navigating tight corners with precision.

Final Audio, with its choice of a relatively small 6.4mm driver, made a similar gambit. A smaller, lighter diaphragm has less inertia. This means it can start and stop moving with incredible speed. In acoustic terms, this translates to excellent transient response. It can precisely reproduce the sharp attack of a snare drum, the delicate pluck of a guitar string, or the subtle nuances of a human voice. This focus on agility is why many users describe the sound as “clear,” “neutral,” and “articulate.” It’s an engine tuned for detail and finesse.

But here lies the first critical trade-off. That nimble engine won’t give you the ground-shaking rumble of a V8. Similarly, the 6.4mm driver, by its physical nature, may not move enough air to produce the deep, sub-bass frequencies that rattle your skull. This is why another group of listeners might describe the sound as “flat” or “lacking in bass.” Neither assessment is wrong. They are simply describing the two faces of a single, deliberate engineering choice: agility was chosen over brute force.

The Drivetrain: The Virtue of Efficiency

An engine is useless without a system to deliver power to the wheels. In our earphone, this is the electrical system, defined by its 16-Ohm impedance and Oxygen-Free Copper (OFC) cable.

Impedance, measured in Ohms, is essentially electrical resistance. A high-impedance headphone is like a race car that requires special, high-octane fuel; it needs a powerful, dedicated amplifier to get the best performance. The E1000C’s incredibly low 16-Ohm impedance makes it the opposite. It’s a hyper-efficient engine that runs beautifully on standard pump gas. It requires very little power to reach a satisfying volume, which is why it works so brilliantly straight from a smartphone, laptop, or portable music player. This wasn’t an accident; it was a decision to make high-fidelity sound democratic and accessible, without requiring extra, expensive gear.

The OFC cable is the fuel line in this system. Standard copper wire contains microscopic oxygen impurities that act like tiny bits of debris in the line, disrupting the smooth flow of the electrical signal. By removing these impurities, the OFC cable ensures the audio signal—the “fuel”—reaches the driver with the least possible distortion. It’s a subtle but crucial element that preserves the purity of the music as it was recorded.

The Chassis and Cockpit: The Unseen Science of Shape and Silence

Now for the body and frame. The E1000C’s housing is made of a lightweight but durable ABS plastic. It might not have the cold, premium feel of machined aluminum, but from a sound engineering perspective, it’s a very clever choice. Metal, being very rigid, can sometimes “ring” with certain frequencies, adding its own unwanted coloration to the sound. A well-designed polymer like ABS, however, has excellent acoustic damping properties. It acts as a lightweight, rigid chassis that is also excellent at absorbing unwanted vibrations, preventing the housing itself from rattling and muddying the sound.

The final touch is the cockpit—the interchangeable silicone eartips. These are fundamental to the experience, providing passive sound isolation. Unlike electronic noise cancellation, which actively fights noise with anti-noise, this is pure physics. A proper seal in the ear canal physically blocks a significant amount of external high-frequency noise, like conversations or traffic hiss. This creates a quiet, controlled environment, allowing the earphone’s engine to perform without interference. It lets you hear the finer details in the music, not because the volume is cranked up, but because the clamor of the outside world has been quieted.

The Final Destination: The Listener’s Brain

We’ve now fully dissected the machine. We understand its agile engine, its efficient drivetrain, and its purpose-built chassis. So why do two people, listening to the same song on the same device, have wildly different experiences?

The answer lies in the most complex audio processor of all: the human brain. This is the realm of psychoacoustics, the study of how we perceive sound. For one, our hearing is not linear. As demonstrated by the famous Fletcher-Munson curves, our sensitivity to different frequencies changes dramatically with volume. At lower volumes, our ears are much less sensitive to low and high frequencies. This is why a perfectly “neutral” earphone can sound bass-light when listening quietly.

Furthermore, the physical shape of our ear canals is as unique as our fingerprints. These unique geometries create their own resonances, subtly amplifying some frequencies and dampening others before the sound even reaches our eardrums. What sounds perfectly balanced to one person might have an annoying peak or dip for another. Add to this our personal preferences—the “internal EQ” we’ve developed over a lifetime of listening—and it becomes clear why a single, objectively engineered product can elicit such a spectrum of subjective responses.

The Final E1000C isn’t a magical device that pleases everyone. It’s a device tuned to a specific target of clarity and neutrality. Whether you perceive this as “accurate and clean” or “boring and flat” depends less on the earphone, and more on the remarkable, unique processor between your ears.

Checkered Flag: The Engineer’s Victory

The Final E1000C is a triumph, not of limitless budget, but of elegant constraint. It doesn’t have the “best” of everything. It has something far more impressive: the right combination of everything. Its success is a testament to a design philosophy where every component is chosen to serve a single, unified purpose—to deliver the clearest, most articulate sound possible within its price bracket.

It reminds us that true engineering excellence isn’t always about reaching for the most expensive parts. It’s about deeply understanding the fundamental laws of physics, acoustics, and materials, and then applying that knowledge to orchestrate a harmonious result from humble components. The real lesson of the E1000C, then, isn’t just about a great pair of affordable earphones. It’s a new lens through which to see the world, a newfound appreciation for the quiet, intelligent design hidden within the everyday objects all around us.