YASEZ in-Ear Headsets: A Feature-Packed Option for Music Lovers

Update on July 3, 2025, 12:18 p.m.

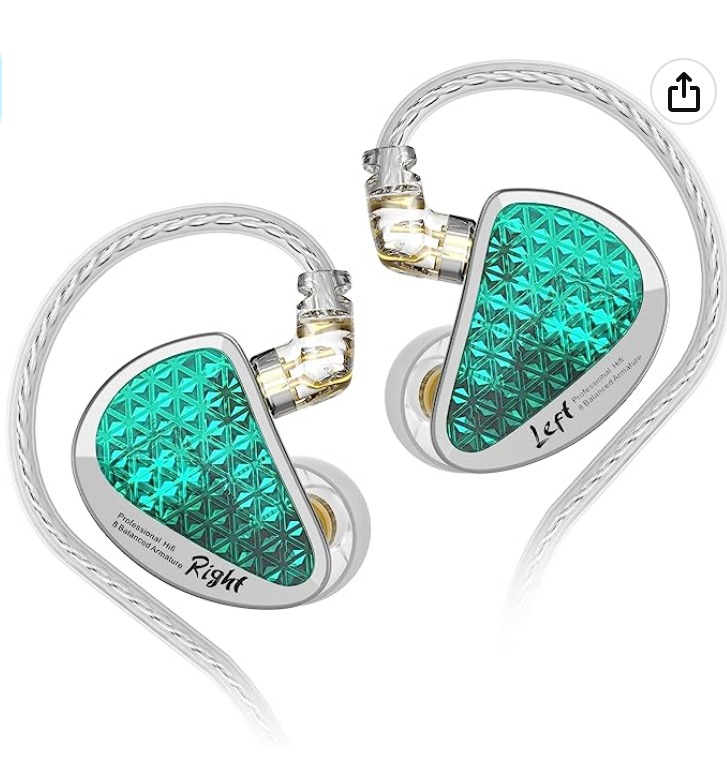

It begins, as so many modern quests do, with a scroll through the endless digital marketplace. You come across a product page: the “YASEZ in-Ear Headsets.” The price, a rather specific $235.20, catches your eye. So does the language. It promises “Full Frequency HIFI Moving Iron.” Below, in the space reserved for the wisdom of the crowd, there is only silence. Zero reviews.

It’s a peculiar artifact of our time. A product with a premium price tag, speaking a cryptic technical language, with no social proof to vouch for its existence or quality. It’s easy to dismiss and scroll on. But what if we didn’t? What if we treated this page not as an advertisement, but as a map to a hidden story? A story about how a piece of medical technology, designed to help people hear the world, was hijacked for rock and roll, and eventually, found its way into your pocket. This isn’t a review of the YASEZ earphones. It’s an excavation of the secrets they claim to hold.

The Whisper Machine

Our story doesn’t start in a booming concert hall, but in a quiet laboratory in the 1950s. The challenge wasn’t to create earth-shaking bass, but to solve a deeply human problem: hearing loss. The world needed a device small enough to fit in the ear, efficient enough to run on a tiny battery for days, and precise enough to reproduce the complex nuances of human speech. The result was a marvel of micro-engineering: the balanced armature driver.

Invented by companies like Knowles, a name still revered in the audio world, the balanced armature (or “moving iron,” as our artifact calls it) was fundamentally different from a traditional speaker. It didn’t use a large, cone-shaped diaphragm to push air. Instead, it used a minuscule, reed-like armature, “balanced” in a magnetic field. When an electrical signal—a voice—was applied, this armature would vibrate with incredible precision, like the needle of a seismograph detecting a faint tremor. These vibrations were then channeled directly into the ear.

It was, in essence, a whisper machine. Its purpose wasn’t power, but fidelity and intimacy. It was a medical instrument designed to restore a fundamental sense, a testament to the idea that the most profound technologies are often the quietest.

Hijacked for Rock and Roll

For decades, this remarkable technology lived almost exclusively in the beige world of audiology. Then, in the 1980s and 90s, it was discovered by a group of people with the exact opposite problem: the world was too loud.

Imagine being a musician on a stadium stage. You’re surrounded by a deafening wall of sound—thundering drums, screaming guitars, and the roar of fifty thousand fans. In this sonic chaos, how do you hear your own voice, your own instrument? This was the crisis that led to a technical revolution. Audio engineers and pioneers, most famously Jerry Harvey of Ultimate Ears, were looking for a solution. They needed an earpiece that could block out the stage noise while delivering a crystal-clear monitor mix directly to the musician’s ear. They needed precision. They needed efficiency. They needed something small. They needed the hearing aid driver.

They took this medical-grade technology and repurposed it. It was hijacked for rock and roll. Custom-molded to an artist’s ear and packed with these tiny balanced armature drivers, the first professional in-ear monitors (IEMs) were born. For musicians, it was transformative. Suddenly, they could hear every note with surgical precision, protecting their hearing while performing better than ever. The whisper machine had learned to sing.

The Sculptor and the Painter

By now, you’re likely wondering what makes this little device so special. To understand, let’s pause our story for a moment and step into the workshop. Think of audio drivers as two different kinds of artists.

The traditional dynamic driver, found in most headphones and speakers, is a passionate painter. It uses a relatively large, piston-like diaphragm, which it pushes back and forth to move a lot of air. It’s brilliant at creating broad, powerful strokes of sound—rich, resonant bass and a grand, atmospheric feel. It paints a beautiful, emotional picture.

The balanced armature driver, our protagonist, is a meticulous sculptor. It works on a much smaller scale. Its moving part, the armature, is nearly weightless. It doesn’t push air so much as it carves the sound waves with a tiny lever. This allows it to move with incredible speed and accuracy. It excels at reproducing fine details, textures, and complex transients—the crisp snap of a snare drum, the delicate decay of a cymbal, the subtle breath of a vocalist. It doesn’t paint a picture; it sculpts a detailed, lifelike statue.

Neither artist is inherently “better”—they simply have different strengths. The painter’s work feels powerful and immersive. The sculptor’s work feels intricate and astonishingly clear. The highest echelons of audio often use both, assigning the dynamic driver to handle the powerful bass and multiple balanced armatures to sculpt the mids and highs.

From the Stage to the Street

Like so many professional technologies, from a chef’s knife to a race car’s engine, what was once the exclusive domain of experts eventually trickles down to the rest of us. The cost of balanced armature drivers came down, and audio companies began putting them in consumer earphones, often in hybrid configurations alongside a dynamic driver. They became a selling point, a mark of “Hi-Fi” aspiration.

This brings our story to the present. The technology born in a lab and forged on the stage is now a feature listed on countless product pages. And as this was happening, another revolution was underway: the severing of the final cord. Bluetooth technology, once a clunky tool for wireless headsets, evolved. Iterations like Bluetooth 5.1, as listed on the YASEZ page, focused on making the wireless link faster to establish and more stable in crowded environments, finally making high-fidelity listening on the go a seamless reality.

Decoding the Artifact

So, let’s look at that mysterious product page one last time. The cryptic phrase “Full Frequency HIFI Moving Iron” is no longer a mystery. It’s a direct claim to a legacy—a legacy of medical precision and rock-and-roll clarity. The technology it references is not a gimmick; it’s a genuinely brilliant piece of engineering with a rich, fascinating history.

But understanding the script doesn’t tell you the quality of the actor. The science and history tell us what a balanced armature driver can do. They cannot tell us how well the one inside this particular $235 plastic shell has been implemented. Is the sculptor’s hand skillful? Is the driver well-tuned, or is it merely a bullet point on a feature list?

That is the unanswered question. The product page, our digital artifact, can take us no further. We have unearthed the story, and the knowledge is, in itself, powerful. It equips us to ask the right questions and to see past marketing jargon. It transforms us from passive consumers into informed listeners. But the final act of discovery—the judgment of sound itself—cannot be delegated. That journey, as it always has been, is reserved for your own ears.