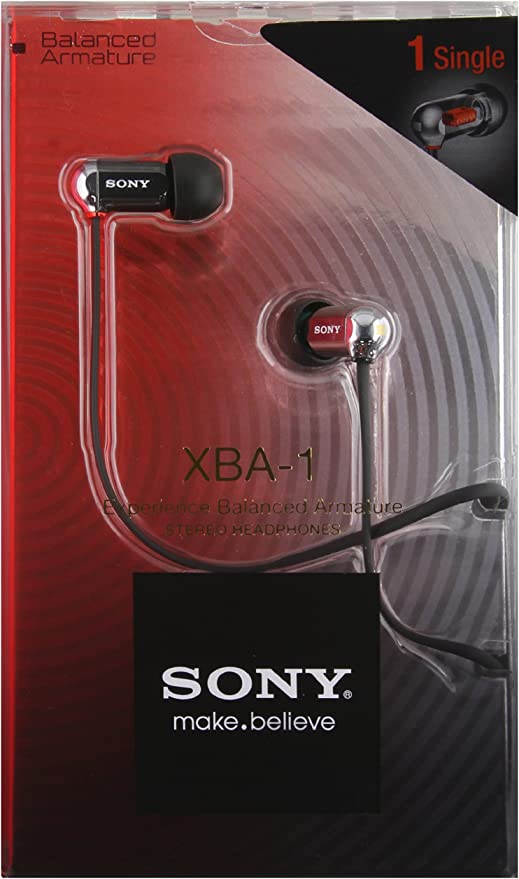

Sony XBA-Z5: Unveiling the Details of High-Resolution Audio

Update on Aug. 24, 2025, 5:32 p.m.

Cast your mind back to 2014. It was a fascinating turning point for personal audio. The convenience of MP3s had long since won the war for portability, but a quiet rebellion was brewing. A growing contingent of listeners, armed with the first generation of dedicated Digital Audio Players (DAPs) from brands like Astell\&Kern, were no longer content with “good enough.” They were searching for sonic truth, for a way to carry the fidelity of a home hi-fi system in their pocket. This was the dawn of the mainstream Hi-Res Audio movement, and it demanded a new class of transducer to unlock its potential.

Into this burgeoning landscape, Sony—a company whose legacy is inextricably linked to portable audio through the Walkman—delivered its statement: the Sony XBA-Z5. More than just an earphone, the Z5 was a piece of ambitious engineering, a physical manifestation of an audio philosophy. Today, looking back at this classic in-ear monitor (IEM) offers more than a dose of nostalgia; it provides a masterclass in the timeless physics, material science, and clever compromises that define high-fidelity sound reproduction.

The Hybrid Conundrum

The fundamental challenge in headphone design is a law of physics: it is exceptionally difficult for a single, lone driver to masterfully reproduce the entire audible spectrum. A deep, impactful bass note requires moving a significant amount of air, demanding a large, robust driver. Conversely, capturing the delicate, high-frequency shimmer of a cymbal requires a driver that is almost weightless, capable of vibrating thousands of times per second with microscopic precision. To ask one driver to be both a heavyweight boxer and a ballet dancer is a near-impossible task.

Sony’s solution with the XBA-Z5 was not to find a jack-of-all-trades, but to assemble a team of specialists. This is the core principle of the Hybrid IEM. It’s an acoustic orchestra in miniature, where each musician is chosen for their unique talent. But assembling this orchestra is fraught with challenges, chief among them being how to make these disparate voices sing in perfect harmony.

Dissecting the Machine: The Heartbeat and the Voice

At the heart of the ZBA-Z5’s architecture lies its audacious trio of drivers, each with a specific role assigned by a carefully tuned crossover network—the orchestra’s silent conductor.

The Bass Engine: The 16mm Dynamic Driver

The soul of the Z5’s low-end performance is its colossal 16mm dynamic driver. For an in-ear monitor, this is enormous. This driver functions as a classic piston, a miniature loudspeaker cone tasked with the brute-force work of creating bass. Its diaphragm is crafted from a material called Liquid Crystal Polymer (LCP). This isn’t a random choice; it’s a calculated decision rooted in material science. To reproduce bass accurately, a diaphragm needs to be incredibly rigid to move as a single, unified surface and resist deforming (an effect known as “breakup”), yet also extremely light to respond instantly to the musical signal. LCP provides this stellar combination of high rigidity and low mass, allowing the Z5 to deliver bass that is not just powerful, but also fast, textured, and controlled.

The Detail Artists: The Dual Balanced Armature System

While the dynamic driver lays the foundation, the mids and highs—the realms of human voice, the snap of a snare drum, the decay of a piano note—are entrusted to a pair of Balanced Armature (BA) drivers. With origins in the medical hearing aid industry, BA drivers are marvels of miniaturization. They operate not by pushing a cone, but by pivoting a tiny, reed-like armature within a magnetic field. Because the moving mass is infinitesimally small, they possess a speed and precision that dynamic drivers struggle to match. They are the soloists of the orchestra, articulating the finest nuances and micro-details in a recording, the very details that Hi-Res Audio promises to deliver. The Z5 uses two of these BAs, allowing one to focus on the core midrange and the other to handle the highest treble frequencies, further refining the detail retrieval.

The Unsung Hero: The Science of the Magnesium Chassis

The Z5’s drivers are housed not in common plastic or aluminum, but in a precisely machined magnesium alloy. This is perhaps the most overlooked aspect of its design, yet it is critical to its performance. Every object has a natural tendency to vibrate, or resonate. In a poorly designed headphone, the housing itself can start to “sing along” with the music, smearing details and adding its own unwanted coloration to the sound.

Magnesium possesses an exceptionally high internal damping factor. In layman’s terms, it is acoustically inert. It kills vibrations quickly and effectively, acting as a silent, stable platform from which the drivers can launch their sound waves. This ensures that what you hear is the pure sound of the music as reproduced by the drivers, not the resonance of the earphone itself. It’s the acoustic equivalent of building a concert hall with perfectly non-reflective walls.

Anatomy of a Flaw: An Engineering Trade-Off

This commitment to acoustic purity, however, came at a price: ergonomics. The most enduring criticism of the XBA-Z5 is its bulky size and how far it protrudes from the ear. This was not an oversight but a conscious compromise. Housing a 16mm dynamic driver, two BA drivers, and the necessary acoustic chambers simply requires physical volume. Sony’s engineers chose to prioritize the acoustic design over a sleek, low-profile fit. The XBA-Z5 is a stark example of the engineering principle of “form follows function,” a design where the demands of performance dictated the physical shape, for better or for worse.

The Final Link: Purity Through a Balanced Connection

Further signaling its audiophile intent, the XBA-Z5 was one of the earlier IEMs to ship with a balanced audio cable. In a standard 3.5mm headphone jack, the left and right channels share a single ground wire. This shared path can act as an antenna for electrical noise and can also lead to “crosstalk,” where a tiny amount of the left channel’s signal bleeds into the right, and vice-versa, subtly collapsing the stereo image.

A balanced connection provides separate, dedicated signal and ground paths for each channel. This allows the audio player’s amplifier to use a technique called common-mode rejection to actively cancel out any interference picked up along the cable. The result is a blacker, quieter background and a more defined and expansive stereo soundscape.

A Technological Time Capsule

Listening to the Sony XBA-Z5 today is a fascinating experience. It stands as a technological time capsule, perfectly preserving the ambitions and engineering philosophies of the early Hi-Res Audio era. While newer designs may offer better comfort or different sonic flavors, the core principles embodied in the Z5—the intelligent division of labor in a hybrid system, the critical role of material science in controlling resonance, and the pursuit of electrical signal purity—remain as relevant today as they were in 2014. It is a reminder that great audio design is not about chasing fleeting trends, but about the masterful application of science to the art of sound.