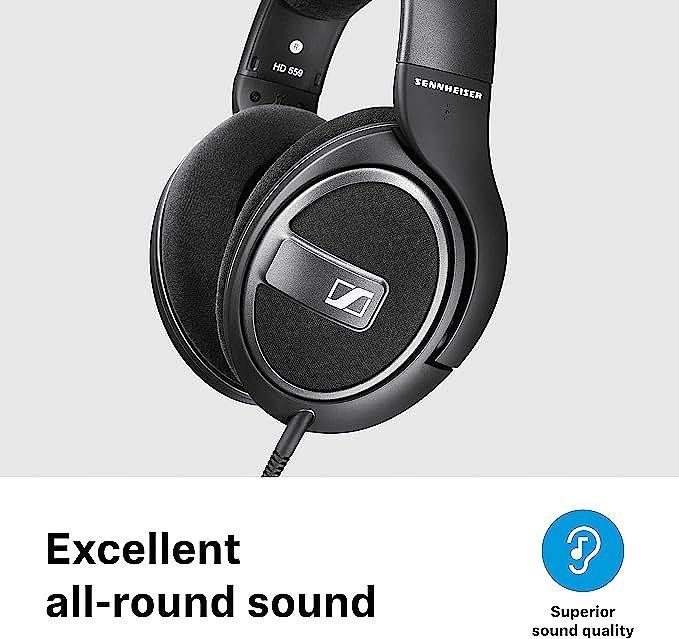

SENNHEISER HD 559 Open Back Headphone - A Remarkable Audiophile Experience

Update on July 4, 2025, 7:29 a.m.

Close your eyes for a moment. Imagine you’re sitting in a barber’s chair. You hear the electric buzz of clippers approaching from your right, the metallic snip-snip of scissors circling behind your head, and the soft rustle of a cape being whisked away. You can almost feel the air move. Now, open your eyes. You’re in your living room, the only thing touching you is a pair of headphones. There was no barber, no scissors. So, what just happened?

You’ve just experienced a profound truth about one of our most essential senses: we do not simply hear the world. Our brain, an astonishingly powerful prediction machine, takes the raw data of sound waves collected by our ears and constructs a complete, three-dimensional reality from them. Hearing is an act of creation. And for the last half-century, a dedicated group of people—audio engineers—have been perfecting the art of building these convincing illusions, these phantom worlds, right inside our heads. Their story, and the science they wield, is far more fascinating than you might think.

The Beautiful Mistake: A Revolution in a Yellow Box

Our journey begins not with a grand plan, but with a happy accident in the late 1960s. Back then, personal listening was a rather claustrophobic affair. Headphones were typically heavy, sealed-off contraptions that clamped onto your head, delivering a sound that felt congested and trapped—like listening to a concert from inside a closet. They isolated you, but they also isolated the music from its soul.

Then, at the Sennheiser labs in Germany, something remarkable happened. A prototype headphone, the story goes, was being tested without its rear enclosures. It was an oversight, a mistake. But when an engineer put it on, the sound was revelatory. It was light, airy, and astonishingly natural. It didn’t feel like it was being injected into the skull; it felt like it was simply… there. By letting the sound waves escape, they had inadvertently set the music free.

That beautiful mistake became the legendary Sennheiser HD 414, the world’s first open-back dynamic headphone. With its iconic yellow earpads, it didn’t just sell millions of units; it shattered the paradigm of personal audio. It proved that to create a vast, realistic soundscape, you first had to tear down the walls. This philosophy is the very DNA of a modern open-back headphone like the SENNHEISER HD 559, and it’s built on three pillars of remarkable science.

The Three Pillars of Sonic Architecture

Think of an audio engineer as an architect, but one who designs invisible structures for your mind. To build a believable “concert hall in your head,” they must master three distinct disciplines.

Pillar I: The Walls That Breathe (Acoustic Physics)

The first pillar is the space itself. A closed-back headphone is like that small, square, perfectly reflective room. Sound waves from the tiny internal speaker bounce off the hard plastic shell, creating a chaotic mess of echoes and reflections. Certain frequencies get amplified, others get canceled out. This phenomenon, known as standing waves, is the enemy of natural sound.

The open-back design of the HD 559 is the architectural equivalent of a Roman amphitheater. The grilles on the outside act as acoustically transparent walls, allowing the rearward energy of the sound wave to radiate out into the open air and decay naturally. This prevents pressure from building up and eliminates those distorting internal reflections. The result is a sound that is clear and uncolored, with a sense of effortless space. It’s the difference between a voice in a box and a voice in a room.

Pillar II: The Faithful Messenger (Transducer Engineering)

If the open design provides the room, the transducer is the orchestra that plays within it. This is the heart of the headphone, a miniature engine converting electrical pulses into physical vibrations. The quality of our illusion depends entirely on its precision. The HD 559 uses a 38mm transducer with an aluminum voice coil, and those details are crucial.

The aluminum voice coil is the “athlete” of the system. Aluminum is incredibly light yet rigid, allowing it to start and stop on a dime, responding instantly to the most subtle details in an electrical signal. This agility is what delivers crisp, clear transients—the sharp attack of a snare drum, the delicate pluck of a guitar string.

The “50-ohm” specification, its impedance, is also a key piece of the puzzle. It relates to the concept of the “damping factor,” which is an amplifier’s ability to control the driver’s movement. Think of it as a skilled conductor’s hand, telling the orchestra precisely when to play and, just as importantly, when to stop. A well-damped driver doesn’t produce unwanted, “muddy” vibrations after the note is supposed to have ended, leading to a much cleaner and more precise performance. The 50-ohm impedance of the HD 559 is engineered to work beautifully with a wide range of devices, achieving this control without demanding a herculean amount of power.

Pillar III: The Brain’s Shorthand (Applied Psychoacoustics)

This is where the real magic happens. Our architect has built a perfect room and hired a flawless orchestra. But how do they convince you, the listener, that the orchestra is in front of you on a stage, and not just playing on a flat line between your left and right ear? They use a clever trick on your brain.

This field is called psychoacoustics, and it’s the study of how we perceive sound. Your brain is a master at locating things in space. It does this, in part, by analyzing the way your outer ears (the pinnae) subtly color the sound before it enters your ear canal. Sounds from the front are filtered differently than sounds from the back or above. Your brain has been learning this code since the day you were born.

Sennheiser’s “Ergonomic Acoustic Refinement” (E.A.R.) technology is a direct application of this principle. The transducers inside the HD 559’s earcups are not mounted flat. They are angled slightly, directing the sound waves to your ear in a way that mimics how you would hear a pair of stereo speakers positioned in front of you. It’s a gentle nudge, a piece of engineered body language that gives your brain a crucial clue. Your brain receives this angled signal and instinctively decodes it as, “Ah, this is coming from a stage in front of me.” This subtle act of engineering transforms a simple stereo image into a believable, three-dimensional soundstage.

The Art of the Possible: Rituals and Realities

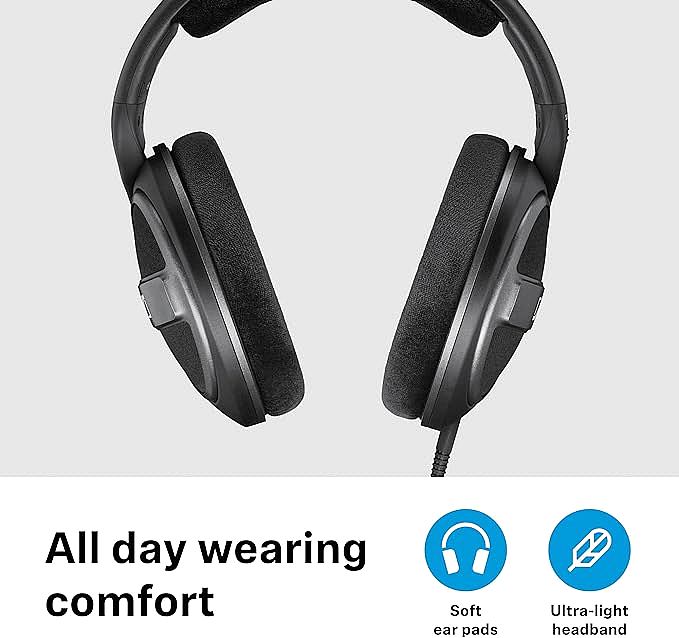

Of course, this architecture of openness comes with a necessary trade-off. The same design that lets sound out also lets the world in. These headphones will not isolate you from the drone of an airplane or the chatter of a coffee shop. Likewise, your music will be audible to those sitting near you. This isn’t a flaw; it’s a feature that defines their purpose. They are not for commuting; they are for communion—a private, focused ritual with your music in a quiet space.

Even the comfort is part of the science. The large, soft velour earpads do more than just feel pleasant. Unlike leather or pleather, velour is a breathable, acoustically porous material. It doesn’t create a sweaty, hermetic seal, which not only allows for hours of listening without physical fatigue but also becomes an integral part of the open acoustic system.

And that robust, 3-meter cable ending in a chunky 6.3-millimeter plug? It’s a subtle nod to the headphone’s heritage. That is the standard connector on studio mixing consoles, amplifiers, and high-fidelity equipment. It’s a physical link to the professional world where the music was recorded, a symbolic bridge from the artist’s creation to your perception.

Beyond Listening, To Perceiving

In the end, a headphone like the SENNHEISER HD 559 is much more than a consumer electronics product. It is a finely tuned instrument, an accessible ticket to a fascinating intersection of history, physics, and human perception. It’s a testament to a beautiful mistake made over half a century ago and the relentless refinement that followed.

So, the next time you put on a pair of open-back headphones, don’t just listen to the melody or the words. Close your eyes and listen for the space. Listen for the architecture. Try to perceive the distance between the instruments, the height of the singer’s voice, the shape of the imaginary room you’re in. You’re not just a passive listener. You are the audience, the concert hall, and the final, crucial component in a beautiful, shared illusion.